The Languages of the Second Age

J.R.R. Tolkien’s Legendarium is a remarkable piece of world-building, even moreso at the time The Lord of the Rings was published than today, when terms such as “world-building” have entered our lexicon, largely through attempts to imitate Tolkien, or some of his many imitators. Tolkien’s Legendarium was and still is notable for its verisimilitude. Although it is not “realistic” as the term is conventionally used in literary criticism, Tolkien’s attention to detail makes it quite believable as a collection of myths and legends of some long-forgotten people.

At the root of this verisimilitude, I would argue, is Tolkien’s careful study of (and sensitivity to) ancient and medieval languages, and the works written in them, without which it is hard to imagine him or any other modern writer coming up with the same kind of result. Humans, with very few exceptions, are immersed in and use language for their entire lives. Although most of us are not linguists or philologists, we do have an intuitive sense of what works and what doesn’t. Tolkien was well aware of this, or at least of how language affected him. In his famous 1951 letter to Milton Waldman, he wrote (referring to his Elven languages, Quenya and Sindarin): “Out of these languages are made nearly all the names that appear in my legends. This gives a certain character (a cohesion, a consistency of linguistic style, and an illusion of historicity) to the nomenclature, or so I believe, that is markedly lacking in other comparable things. Not all will feel this as important as I do, since I am cursed by acute sensibility in such matters.” The development of “constructed languages” has since become a significant component of world-building, but it seems to me that few other notable authors measure up to Tolkien in this aspect.

If it is a challenge for builders of other worlds to measure up to J.R.R. Tolkien in his use of language, the same challenge applies as well to those who wish to play in Tolkien’s own sandbox, and here any difference in quality will be all the more noticeable for existing in the same secondary world. As Amazon Studios ramps up the marketing campaign for The Rings of Power, which is due to be released in a little more than four months, one thing I am looking forward to is how Amazon makes use of Tolkien’s language, languages, and nomenclature, and how well it fits with Tolkien’s existing writings. Of course, there’s no accounting for taste, and different people will have different views, but what feels out of place to one well-versed Tolkien fan will likely have the same effect on many other fans as well.

Before continuing much further into a discussion of Amazon Studio’s use of Tolkien’s language and languages, it will be helpful to examine what Amazon Studios has to work with—that is, information about languages and the Second Age from Tolkien’s existing writings. The information we have about the Second Age in general is rather brief. Apart from a few brief narratives such as “Aldarion and Erendis: The Mariner’s Wife” (in Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth) and “Tal-Elmar” (in The History of Middle-earth, vol. XII: The Peoples of Middle-earth), most information on the Second Age is in the form of a historical chronology with little to no dialog. There is significant information on some of Tolkien’s languages, but not necessarily as they were used in the Second Age. Nevertheless, it is possible to form a reasonably detailed picture of the language situation in the Second Age, as Tolkien conceived it, and therefore, what languages we might expect Amazon Studios to make use of.

A slight disclaimer, before I continue: Although I am a linguist by education, most of my experience is with historical languages. I am not an expert in any of Tolkien’s invented languages, although I appreciate the effort he put into them, and often see similarities between features of his languages and those of real-world languages, albeit combined in new and unique ways.

Elvish

Tolkien developed at least the beginnings of numerous Elvish languages and dialects, but he devoted most of his attention to only two languages: Quenya and Sindarin. We are certain to see names in both of these languages in the show, and we may also hear them spoken or sung as well. Although Tolkien spent much time developing both of these languages, neither is complete to the point that it could be used for everyday speech. For this reason, those who wish to write original dialog in these languages often need to invent words that Tolkien himself did not create. This was the case with the New Line films directed by Peter Jackson. Quenya and Sindarin with non-Tolkienian additions are commonly referred to as “neo-Quenya” and “neo-Sindarin”. In addition, we may possibly hear other forms of Elvish spoken, although Amazon Studios would need to develop them to a greater extent than with Quenya and Sindarin.

Quenya

Quenya, also known as “High-elven”, was the first of the Elvish languages that Tolkien created, beginning around 1915, making it older than any part of his Legendarium, apart from his earliest poems about Éarendel (whose Old English name eventually became the Quenya name Eärendil, or “devoted to the Sea”). Tolkien developed several slight variants of Quenya, but his most well-developed form of Quenya, and the one most likely to be relevant to Middle-earth and Númenor in the Second Age, is Ñoldorin Quenya, also known as Exilic Quenya. (The Ñ is pronounced as ng in English “sing”, but Tolkien fans often pronounce and spell it as N.) This was the language spoken by the Ñoldor, a group of Elves who went West to Valinor, but returned to Middle-earth to do battle with Morgoth (the original Dark Lord, and Sauron’s master at the time) in the First Age. Some well-known Quenya words and phrases include Elen síla lúmenn’ omentielvo (“A star shines on the hour of our meeting”), Aiya Eärendil elenion ancalima! (“Hail, Eärendil, brightest of Stars!”), and Namárië! (“Farewell!”).

Many notable Elves of the Second Age were Ñoldor, or at least had Ñoldorin heritage, including Galadriel, Gil-galad, Celebrimbor (at least, in the version recorded in Appendix B of The Lord of the Rings), and Elrond. Note, however, that all of these names are Sindarin. When the Ñoldor returned to Middle-earth, they eventually adopted the Sindarin language spoken by the Elves they found there. During the Second Age Quenya was a dead language, like Latin, in Middle-earth, though it was still used for some purposes. However, it was the native language of many of the Ñoldor, including Galadriel, who may still have used it among themselves in private. Nevertheless, Sindarin became the lingua franca of the Elves in Middle-earth, even among the Ñoldor. In the Second Age the Ñoldor in Middle-earth lived primarily in Lindon (where the Grey Havens are located), Eregion (next to Khazad-dûm, or Moria), and Imladris, or Rivendell.

There is one other notable group who made use of Quenya in the Second Age: the Men of Númenor. These Men had been known as the Edain in the First Age, living among the Elves and fighting with them against Morgoth. At the beginning of the Second Age they were granted the island of Númenor to live on, and Elros Half-elven, brother of Elrond became their first king, making the choice to live a mortal life. Although they primarily spoke Adûnaic (a Mannish language) and Sindarin, they also used Quenya for certain formal and ceremonial purposes. The placenames of Númenor (e.g. Armenelos, Rómenna, and Andúnië) are Quenya, as are the regnal names of most of the Ruling Kings and Queens of Númenor (e.g. Tar-Minyatur, Tar-Aldarion, Tar-Telperiën, and Tar-Palantir). In addition, many Númenóreans had Quenya personal names, including Elendil, Isildur, Anárion, and Míriel.

Sindarin

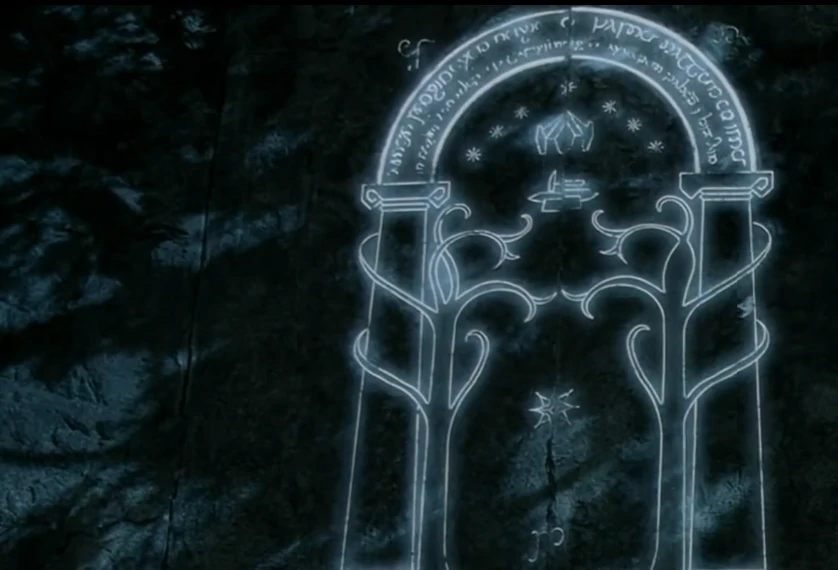

Sindarin was the language of the Sindar, or “Grey Elves”, who made the journey west towards Valinor, but stopped before crossing the Great Sea Belegaer. Although “Sindarin” is itself a Ñoldorin Quenya word, many of the Ñoldor who returned to Middle-earth adopted the language of the Sindar, and even were commonly known by Sindarin names. Some well-known examples of Sindarin include the Hymn to Varda/Elbereth, A! Elbereth Gilthoniel! (“O! Elbereth Star-kindler!”); Glorfindel’s cry to his horse, Noro lim, noro lim, Asfaloth! (“Run swift, run swift, Asfaloth!”); and the inscription on the Doors of Durin:

Ennyn Durin aran Moria:

pedo mellon a minno.Im Narvi hain echant:

Celebrimbor o Eregion teithant i thiw hin.“The Doors of Durin, Lord of Moria:

say ‘friend’ and enter.I, Narvi, made them:

Celebrimbor of Hollin drew these signs.”

Notable Elves of the Second Age who were Sindar include Círdan the Shipwright, Galadriel’s husband Celeborn (according to the published Silmarillion), Oropher and his son Thranduil of the Woodland Realm, and Amdír and Amroth of Lórinand (later Lothlórien). During the First Age the Sindar lived in Beleriand, but the land was mostly destroyed and submerged during the War of Wrath that ended the First Age. During the Second Age some Sindar lived in Lindon, particularly Harlindon (“South Lindon”), under Gil-galad, who was High King of the Ñoldor, as well as other places settled by the Ñoldor. Others left Lindon and settled in Lórinand, the Woodland Realm, and the haven of Edhellond in what later became Gondor.

During the Second Age, Sindarin was the common language used by the Elves in the West of Middle-earth, and it was used by them almost universally for personal names and placenames. The language is typically referred to simply as “Elvish” in The Lord of the Rings. In addition to the Elves, Sindarin was spoken as a native language by some Númenóreans, particularly those who lived in and around Andúnië in the western part of the island.

Nandorin

The Nandor were a group of Elves, closely related to the Sindar, who also began the journey west to Valinor, but stopped short. One group of Nandor, the Laiquendi, or “Green-elves”, eventually did arrive in Beleriand with their Sindar cousins. The land they settled became part of Lindon after the destruction of Beleriand, but not much is known about them in the Second Age. Some of them may have remained in Lindon, some seem to have moved east to Eriador, and some may have rejoined their Nandor cousins east of the Misty Mountains. These Nandor, who did not cross west of the Misty Mountains, settled primarily in Lórinand or the Woodland Realm. They were also known as “Silvan Elves” or “Wood-elves”. In the Second Age, their realms came to be ruled by Sindar, and Sindarin became the common speech among them, although Nandorin was still spoken.

Unlike Quenya and Sindarin, Nandorin is not well developed as a language. In fact, it does not really exist apart from a few proper names, some of which were likely originally intended to be Sindarin, but reimagined by Tolkien as of Nandorin origin or form. Such names include Legolas (“Green-leaf”), which would be Laegolas in standard Sindarin, and Amroth (“Up-climber”), which would be Amrath in standard Sindarin. Two of the numerous names of Lothlórien are also Nandorin: Lórinand (“Valley of Gold”) and Lindórinand (“Vale of the Land of Singers”).

Tolkien does not mention any Silvan Elves who were particularly notable during the Second Age, unless one goes by Tolkien’s early conception of Celeborn as a Silvan Elf. The rulers of Lórinand and the Woodland Realm were of Sindarin origin. Some named Silvan Elves who were likely alive during the Second Age, but are known from the Third Age, were Nimrodel of Lórinand and Galion, Thranduil’s butler in the Woodland Realm.

Avarin

The Avari (“the Unwilling” in Quenya) were a large group of Elves who refused to begin the journey west to Valinor. These Elves developed at least six separate languages, which are collectively referred to as “Avarin”. These languages are also wholly undeveloped, apart from a single word from each. This word is the name of each tribe. The six tribes of Avari known to exist in the Third Age called themselves the Kindi, Cuind, Hwenti, Windan, Kinn-lai, and Penni. These tribal names are all cognate with the Quenya word Quendi, which Quenya-speakers used to refer to all Elves in general.

The names of very few Avari are known, and none at all from the Second Age. The “Dark Elf” Eöl from The Silmarillion could be an Avar, although he could also be a Sinda or Nando. Most Avari remained east even of the Woodland Realm, but some later moved westward. Amazon Studios may choose either to ignore them or to feature them as part of its exploration of “the furthest reaches of the map”. Some fans have speculated that Arondir is an Avar, despite his description by Vanity Fair as a “silvan elf”. His name appears to be Sindarin, however. Or possibly it is Nandorin.

Dwarvish

The Dwarves were taught to speak by Aulë, one of the Valar (similar to angels or demi-gods). Their language was called Khuzdul, and it changed very slowly. There were seven clans of Dwarves, and some developed different dialects, but their language remained mutually intelligible. The Dwarves regarded Khuzdul as a language private to themselves, and generally adopted the languages of Men for public use. They even kept their Khuzdul names secret, adopting names from the languages of the Men around them. Only a few Khuzdul personal names are known, all from the First Age. Even the name of Durin I “the Deathless”, the first Dwarf, came from a Mannish language. Notable Dwarves of the Second Age include Durin III, who received one of the seven rings given to the Dwarves, and Narvi, who made the Doors of Durin and was a friend of the Elf Celebrimbor.

Khuzdul is not as well developed as Quenya or Sindarin, but it is more developed than the Nandorin or the Avarin languages. One of the most well-known examples of Khuzdul is the Dwarves’ warcry, Baruk Khazâd! Khazâd ai-mênu! (“Axes of the Dwarves! The Dwarves are upon you!”). Part of the inscription on Balin’s Tomb is also in Khuzdul, although the proper names “Balin” and “Fundin” are not: Balin Fundinul Uzbad Khazaddumu (“Balin Son of Fundin, Lord of Moria”). Most other examples of Khuzdul are placenames, such as Gundabad (meaning unknown, but possibly containing the root word gundu, “underground fortress”), Zirakzigil (“Silvertine”), Azanulbizar (“Dimrill Dale”), Kheled-zâram (“Mirrormere”), and of course, Khazad-dûm (“Dwarrowdelf”, or “Dwarf Delving”, later known as “Moria”).

The Black Speech

The Black Speech was devised by Sauron during the Second Age with the intention of being used by all who served him. As was often the case with Sauron’s plans, things did not turn out quite the way he had expected. Nevertheless, the Second Age (more specifically, the Dark Years in the latter half of the Second Age) was the heyday of the Black Speech. By far the most well-known passage in the Black Speech is the inscription on the One Ring:

Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul,

ash nazg thrakatulûk, agh burzum-ishi krimpatul.“One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them,

One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.”

This was in the pure Black Speech as devised by Sauron. After Sauron’s defeat in the War of the Last Alliance, the pure Black Speech ceased to be the universal language of the Orcs and other servants of Sauron, but many words from it were borrowed into the various Orc dialects. Most examples of the Black Speech are single words or names, such as Nazgûl (“Ringwraith”), Uruk-hai (“large fighting Orc”), Snaga (“Slave”), Tark (“Man of Gondor”, although this seems likely borrowed from Westron tarkil), and many personal names of Orcs, such as Grishnákh, Shagrat, and Uglúk.

Speakers of the Black Speech include Sauron, the Nine Ringwraiths, and various Orcs, Trolls, and Men who followed Sauron. Given that the Dark Years took place over nearly two thousand years—at least in Tolkien’s chronology—it stands to reason that some of Sauron’s followers, including even some Men, spoke the Black Speech as their native language. The only named Ringwraith, Khamûl, was an Easterling, presumably from the area around the Sea of Rhûn. It may be possible that his name is the sole example of an Easterling word or personal name invented by Tolkien, except possibly for the placename Khand. (The Easterlings of the First Age were a different group of people, not from Rhûn.) On the other hand, it may be that Tolkien intended for Khamûl to be a name in the Black Speech, either his given name as a native speaker of the Black Speech, or a name he adopted or was given as a follower of Sauron.

Tolkien purposely developed the Black Speech to be a language that was phonetically unattractive to himself, so he did not bother to develop it very far. The Black Speech was used in the New Line films, particularly in The Hobbit films, and it was necessary to add to the language to create a sort of “neo-Black Speech” in order to fill out the dialog.

Mannish

Men spoke many languages, not all of them necessarily closely related. However, several different language groups can be determined: 1) Adûnaic and related languages, 2) Haladin and related languages, 3) Drúedain languages, 4) Easterling languages, 5) Haradric languages, and possibly 6) Forodwaith languages. Of these, most are not well-developed at all, the primary exception being Adûnaic. On the other hand, some of these languages (e.g. Rohirric) are more well-developed than any of Tolkien’s languages, simply because they are, in fact, historical languages.

Adûnaic

In the First Age, three Houses of Men moved into Beleriand and became friendly with the Elves. In Sindarin the Elves called them simply Edain, or “Men” (Atani in Quenya). Two of these houses, the House of Bëor and the House of Hador, spoke closely-related languages, which were also related the languages spoken by the Middle Men of Eriador and the Northmen of Rhovanion. These languages, particularly the language of the House of Hador, formed the basis of Adûnaic, the “Language of the West”. As was the case with the Black Speech, the Second Age was the heyday of Adûnaic. In Númenor the majority of people spoke Adûnaic, both noble and commoner alike. As described above, the Elven languages, both Sindarin and Quenya, were known by the well educated, and in the western part of Númenor people spoke a form of Sindarin natively. In addition to Sindarin, some people in the west of Númenor also spoke a Bëorian dialect of Adûnaic.

After Quenya and Sindarin, Adûnaic may be the most well developed of Tolkien’s languages, although it is much less well developed comparatively. Despite that, very few examples of Adûnaic exist apart from proper names. These names are the most recognizable examples of Adûnaic in Tolkien’s works. Some of the latter Kings of Númenor dropped the use of Quenya regnal names in favor of Adûnaic regnal names. Such monarchs include Ar-Adûnakhôr (“King Lord of the West”) and Ar-Pharazôn (“King Golden”). Also, the heiress Míriel (“Jewel Daughter” in Quenya) was given the regnal title Ar-Zimraphel (“Queen Jewel Daughter”). Other notable people with Adûnaic names include Inzilbêth, the Faithful mother of Tar-Palantir. But perhaps the most well-known example of the Adûnaic language is Akallabêth (“the Downfallen”, Atalantë in Quenya), referring to the ultimate fate of Númenor. The longest example of Adûnaic is the “Lament of Akallabêth”, the final lines of which are:

adûn izindi batân tâidô ayadda

îdô katha batîna lôkhî

êphalak îdô Yôzâyan

êphal êphalak îdô hi-Akallabêth“In the West there was once a Straight Road;

now all ways are bent.

Far away now is the Land of Gift.

Far, far away now is the Downfallen.”

Many, but not all of the notable people from Númenor spoke Adûnaic as a native language. Likely such notables as Míriel and Pharazôn, and other members of the royal family spoke Adûnaic natively. The primary exceptions were the Lords of Andúnië and their people in the west of the island, who spoke mostly Sindarin. This would include Elendil and Isildur.

Westron

Westron, or the Common Speech, developed from the Adûnaic spoken in the coastal city of Pelargir, built in the year 2350 of the Second Age. After the Downfall of Númenor nearly a millennium later, the Faithful, led by Elendil, founded the Kingdoms of Arnor and Gondor in the Westlands of Middle-earth. Although the Faithful consisted largely of Sindarin speakers, they found that the inhabitants of Middle-earth, including many who were of Númenórean descent, did not speak Sindarin, and they found it more convenient to use Westron as a sort of lingua franca with which to communicate with those people who were already in Gondor and Arnor. By the end of the Third Age, Westron was commonly spoken from Eriador to Gondor, and even in Rhovanion. Even many Orcs spoke Westron. In the Second Age, however, it is doubtful whether Westron was regarded as a much more than a dialect of Adûnaic. Indeed, the name of Westron in Westron is Adûni.

Despite the importance of Westron in the latter Third Age (when The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings take place), Tolkien did not do much to develop it as a language, beyond inventing a few names and words. The reason for this is that, according to Tolkien’s conceit when writing The Lord of the Rings, he had “translated” the work from Westron to Modern English. Thus, any Modern English that appears in the book is actually translated Westron, and almost all of the Westron has been translated into Modern English, with the exception of a few words and names listed in the Appendices. Tolkien took this conceit so far that even the non-Khuzdul portion of the inscription on Balin’s tomb is actually just Modern English written in cirth (Elf/Dwarf runes), not “actual” Westron. Some examples of actual Westron words include banakil (“halfling”), kuduk (“hobbit”), and tarkil (“Dúnadan”), although tarkil is ultimately of Quenya origin. Westron placenames include Sûza-t (“The Shire”), Branda-nîn (“Border-water”, or “Brandywine”), Karningul (“Rivendell”), and Phurunargian (“Dwarrowdelf”, or “Moria”). Westron personal names include Bilba Labingi (Bilbo Baggins), Maura Labingi (Frodo Baggins), Banazîr “Ban” Galpsi (Samwise “Sam” Gamgee), Razanur “Razar” Tûc (Peregrin “Pippin” Took), and Kalimac “Kali” Brandagamba (Meriadoc “Merry” Brandybuck).

Many important figures of the Third Age spoke Westron as a native language, but there seem to be no prominent figures of the Second Age who were native Westron speakers, if Westron is considered separate from Adûnaic.

The Languages of Eriador and Rhovanion

Almost nothing is known of the languages of the Men of Eriador and Rhovanion during the Second Age, except that they were related to Adûnaic. When the Men of Númenor returned to Middle-earth in the year 600 of the Second Age, 880 years after the first of the Edain crossed the Blue Mountains into Beleriand, they found that many of their words were still recognizable, and they were able to communicate about simple matters. For this reason the Númenóreans recognized the Men of Eriador, and later the Northmen of Rhovanion, as “Middle Men” or “Men of Twilight”, somewhat distant relations of the Edain, distinguishing them from the “Men of Darkness” who tended to oppose them and favor Sauron.

Nothing of the languages of the Men of Twilight is known from the Second Age, except possibly the outer names of some Dwarves, such as Durin and Narvi. However, Tolkien’s conceit of representing Westron by Modern English extended to representing the languages of the Northmen of Rhovanion in the Third Age by languages closely related to Modern English. In The Hobbit Tolkien had casually used Old Norse names for Gandalf and the thirteen Dwarves. This was fine because he created the story for his children, and did not set it in any specific time or place. When he began to write The Lord of the Rings, however, he tried to figure out how to tie the events of The Hobbit into his greater Legendarium. As he developed the history of the Rings of Power, and of Númenor, it became clear to him that Old Norse (ca. A.D. 700-1400) names would be anachronistic in that setting. So he hit upon the idea that the relationship between, say, the language of Dale and Westron, could be represented by the relationship between Old Norse and Modern English. Thus, just as Modern English is a “translation” of Westron, Old Norse is a “translation” of the language of Dale. This idea also allowed Tolkien to include other Germanic languages in The Lord of the Rings. The language of the Rohirrim was represented by Old English. In the Appendices the proper names of the Kingdom of Rhovanion (southeast of Mirkwood) are represented by an ancient Germanic language, probably Gothic, albeit a Latinized Gothic (as if recorded by Gondorian scribes). And the proper names of the Éothéod (who became the Rohirrim) after the fall of the Kingdom of Rhovanion and before Frumgar, or perhaps even Léod (with rulers such as Marhwini and Forthwini), seems to be represented by a hypothetical ancestor of Old English, such as Proto-West Germanic, or North Sea Germanic (Ingvaeonic). Tolkien did not do anything similar with the language of the Men of Eriador, because after being part of the Kingdom of Arnor and its successor kingdoms for much of the Third Age, they mostly spoke Westron.

Given the above, someone wishing to represent the language of the Northmen in the Second Age might use an ancestor of the Germanic languages mentioned above. The problem is that Gothic is already the oldest recorded Germanic language, apart perhaps from some runic inscriptions that resemble the reconstructed Proto-Germanic language. Proto-Germanic is an immediate descendant of Proto-Indo-European, so the most likely candidates to represent the language of the Northmen before the Third Age would be either of those two, preferably Proto-Germanic, as Proto-Indo-European is also the ancestor of the Celtic languages, which also have representation in Tolkien’s works, as we shall see shortly. As an example, if we take the Amazon Studios character Halbrand’s name to be Old English Hálbrand, then his name in Proto-Germanic would be Hailabrandaz. Of course, this may be stretching Tolkien’s conceit a bit too far, and perhaps a better course of action would be to develop a language similar to Adûnaic to depict what the “actual” language of the Northmen might sound like, assuming that one wishes to represent them at all. There are no known notable figures of the Second Age who were Northmen or Men of Eriador.

Haladin and Related Languages

The House of Haleth spoke a language that was markedly different from that of the Houses of Bëor and Hador. The people of Haleth (also called “Haladin”) were largely destroyed during the First Age. Some survivors joined the rest of the Edain to settle on Númenor, but their language likely disappeared entirely. For this reason, when the Númenóreans visited Middle-earth and made contact with the distant relatives of the House of Haleth, they did not recognize them as “Middle Men” or “Men of Twilight”, as they did the Men of Eriador and Rhovanion. The relatives of the Haladin lived primarily near the White Mountains in what later became Rohan, as well as in the regions of Minhiriath and Enedhwaith south of Eriador. These people became the ancestors of the Dunlendings, the Dead Men of Dunharrow, and the Men of Bree.

Tolkien recorded few actual words of any of these languages, apart from the Dunlending word Forgoil (“Strawheads”, an epithet applied to the Rohirrim). It is possible that the language of Tal-Elmar, of which Tolkien recorded a few names and the term Go-hilleg (“Númenóreans”), is also related to this group of languages, as well as various native Gondorian placenames that did not derive from the Elvish or Adûnaic languages, such as Eilenach, Erech, Lamedon, and Lossarnach. However, Tolkien did extend his conceit of using historical languages to “translate” placenames of Bree-land, as well as personal names of various Hobbits of Buckland, into Medieval Welsh in the latter case, or Anglicized Brythonic in the former case. The Bree-landers came northward to Bree during the Dark Years of the Second Age, and were presumably related to the people of Enedhwaith and the Men of the Mountains. Likewise, Buckland was settled largely by Stoors, a group of Hobbits that had lived on the borders of Dunland for some time before migrating to the Shire.

There were few, if any, notable Men who were natives of any part of Middle-earth during the Second Age. Even Tal-Elmar, wherever in Middle-earth he was from, does not seem particularly notable, at least from what little Tolkien wrote about him. That said, those peoples who were related to the Haladin collectively played a rather significant part in the history of the Second Age. The people of Enedhwaith were among the first to feel the effects of Númenórean colonization, not just trade, as the Númenóreans cut down their forests. This led them into conflict, even causing them to side with Sauron, at least temporarily, during the War of the Elves and Sauron. Another related group of people were the Men of the Mountains, who promised to aid Isildur, but ended up breaking their oath and falling under Isildur’s curse.

Given Tolkien’s use of Celtic languages to represent the ancestral languages of the Bree-landers and Dunlendings, it might make sense to use an ancestral language to represent the inhabitants of Enedhwaith (sometimes called Gwathuirim) during the Second Age. I would propose either Common Brittonic or Proto-Celtic. Or an entirely new language could be devised, but it would need to be created pretty much from scratch, given how little Tolkien developed the language of the people of Haleth or their kin who lived east of Beleriand.

Languages of the Drúedain

The Drúedain were a group of Men, also known as “Woses”, or “Wild Men of the Woods”. They generally lived away from civilization and other Men, but some Drúedain became friendly with the Haladin and accompanied them to Beleriand in the First Age. The descendants of these Drúedain also settled in Númenor. However, foreseeing the decline of Númenor into evil ways, they began leaving the island. Most of the Drúedain lived around the White Mountains.

Tolkien recorded few words of the language of the Drúedain. Nevertheless, it is more developed than many Mannish languages. The name for the Drúedain in their own tongue was Drughu. Their word for Orcs was gorgûn. There are also two named Drúedain: Aghan from the First Age, and Ghân-buri-Ghân from the Third Age. (Apparently buri means “son of”.) No named Drúedain are known from the Second Age.

Languages of the Easterlings

The term “Easterling” appears to refer to at least two different groups. In the First Age a group of Men referred to as “Easterlings” crossed the Blue Mountains and entered Beleriand after the Three Houses of the Edain. They were presumably so-called because they came from somewhere east of the Blue Mountains. Eriador is immediately east of the Blue Mountains, and they may have been residents of Eriador before crossing into Beleriand. The “Easterlings” of the Third Age, on the other hand, were a group (or several groups) of people who invaded Gondor from the East from time to time. Their homeland was around the Sea of Rhûn. In the Third Age they rode horses and horse-drawn wagons and chariots, and seem to have had a nomadic culture similar to those of the Eurasian Steppes. In the early Second Age, Sauron lived among the Men of the East and grew his power base there before moving to Mordor to counter the growing influence of the Númenóreans.

Few, if any, words or names of the Easterlings of the Second and Third Ages are known. The most notable Easterling, and the only Easterling (of Rhûn) given a name, is Khamûl, one of the Ringwraiths. His name may be from an Easterling language, but it could also possibly be in the Black Speech. Then again, given Sauron’s association with the Men of the East in the early Second Age, it is possible that he used an Easterling language as the basis for the Black Speech. The name of the land of Khand is of unknown origin, but given its proximity to the lands of the Easterlings, it may possibly be from an Easterling language. The word “Variag” is also associated with Khand. It may be interpreted as a word from the language of Khand, which may be related to the Easterling languages. However, it is likely that Tolkien intentionally borrowed the word from “Varyag”, the Slavic term for the Varangians, Vikings who often served as mercenaries to Slavic or Byzantine employers.

An Easterling language would have to be built up from very few words, perhaps also inspired by historical languages of Eastern Europe or Central Asia. However, it is interesting to note that Tolkien developed a language called Mágol, or Mágo, which was based on Hungarian. He tried to fit it into his Legendarium as the language of the children of Húrin, then considered making it a language of Orcs, before abandoning the idea. (He did, however, obtain the Orc name “Bolg” from this language.) The language is not very well developed, but it could be repurposed as an Easterling language.

Languages of the Haradrim

The Haradrim were those people (apart from the descendants of the Númenóreans) who lived south of Gondor and Mordor. They seem analagous with the peoples of the Middle East and Africa. Few words of any Haradric language are attested. The name of the ancient port city of Umbar may have been taken from a Haradric language. Much later, at the end of the Third Age, the words mûmak (“elephant”) and mûmakil (“elephants”) are from a Haradric language. Also, Gandalf the Grey was known as Incánus in the South. Although the name is clearly Latin (for “gray-haired”), Tolkien at one point attempted to retcon it as being derived from a Haradric language, in which inkâ-nûs means “North spy”. At other points he also attempted to explain it as a Quenya or Westron name by which Gandalf was known in Gondor.

No Haradrim are known by their personal name, in the Second or any other Age, and no Haradric language is well developed. There are a few Haradric words that could form the basis for a language, but most of the language would need to be invented.

Languages of the Forodwaith

The Forodwaith, whose descendants were known as the Lossoth, or the Snowmen of Forochel, lived to the north of Eriador. In the Third Age they knew some Westron, implying that it wasn’t their native language. Presumably they had their own language or languages, but nothing is recorded of it, not even any proper names. Any language of the Forodwaith would need to be wholly invented, though perhaps using Finnic, Ugric, or Siberian languages as a basis.

Halfling Languages

The Hobbits, or Halflings, seem not to have ever had their own language. According to the Prologue (“Concerning Hobbits”) of The Lord of the Rings, “[o]f old they spoke the languages of Men, after their own fashion”. In the mid-Third Age they seem to have spoken the same language as the other Men of the Vales of Anduin (represented by Old English), notably the Éothéod, who nevertheless moved into the area after the Hobbits had already left (with the exception of Sméagol’s folk). In the latter Third Age the Hobbits spoke Westron, or at least a Hobbitish dialect thereof, albeit with some survivals from the speech of the Vales of Anduin. In the Second Age nothing is known of the Halflings except that they probably existed somewhere in Middle-earth. Presumably they spoke a Mannish language, but what language they spoke would depend on where they lived at the time. Tolkien doesn’t give us much to go on, and so far all we know from Amazon Studios’ adaptation is that the Halflings seem to be wandering; but from where to where we do not know so far. Nothing is known of the Halflings’ language or languages of the Second Age, and no notable Halflings are known from that time.

Amazon Studios and Tolkien’s Linguistic Legacy

Although little is yet known about Amazon Studio’s use of Tolkien’s invented languages, some things are known for certain. From both official information and rumors that have been revealed so far, it is apparent that Amazon will make use of both Sindarin and Khuzdul writing in the visual imagery of the show, as well as Quenya and likely Sindarin names. It is likely that we will also hear spoken Sindarin, Khuzdul, and likely Quenya as well. Adûnaic will also likely feature at some point in scenes set in Númenor. And, of course, no doubt Amazon will make use of the Black Speech of Mordor at some point in the series. It seems less certain to me whether Amazon Studios will make use of any of Tolkien’s other invented languages (some consisting of as little as a single word), or any of the historical languages he made use of. There is even a possibility that they will invent their own language or languages for the purpose of the show. I don’t see that as a bad thing, necessarily. It is a necessary aspect of creating a show set in the Second Age. Even in many cases where Tolkien left us some information about a language, in most cases it would still need to created pretty much from the ground up. What’s important, in my opinion, is that it be done with knowledge, with attention to detail, and with an effort to fit well into the existing lore.

No Comments