The Consolation of Philosophy

“If you want to be a philosopher, write novels.”

―Albert Camus

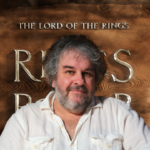

One decade ago, with the release of New Line Cinema’s The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey imminent, Christopher Tolkien gave a rare interview to French newspaper Le Monde. In it he expressed the sense of alienation he had felt from the fan culture that had sprung up around his famous father’s two most well-known works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, particularly as Tolkien fandom had exploded in the wake of the films directed by Peter Jackson. Christopher did not approve of the way the films had adapted his father’s works:

“They eviscerated the book by making it an action movie for young people aged 15 to 25,” Christopher says regretfully. “And it seems that The Hobbit will be the same kind of film.”

Of course, the books themselves had a fair amount of action, though their descriptions of such events as the Battle of the Hornburg (Helm’s Deep) and the Battle of Five Armies were not anywhere near as lengthy as what Peter Jackson filmed. As a scholar of Ancient and Medieval history, as well as a veteran of war himself, Tolkien expertly worked battles into his stories, but felt no need to dwell on the details. But perhaps of even more concern to Christopher Tolkien:

“The chasm between the beauty and seriousness of the work, and what it has become, has overwhelmed me. The commercialization has reduced the aesthetic and philosophical impact of the creation to nothing. There is only one solution for me: to turn my head away.”

Light and High Beauty

It is interesting to compare the vast gulf that exists between the first Tolkien fan and those who came much later to Tolkien fandom, through the films. People who were previously unfamiliar with Tolkien’s works were often struck by the earnestness and seriousness of the films, despite the occasional antics of Merry and Pippin, or Gimli. As for philosophy, quotes from the film often became words to live by. The most popular, of course, are these words spoken by Gandalf to Frodo in The Fellowship of the Ring:

‘I wish it need not have happened in my time,’ said Frodo.

‘So do I,’ said Gandalf, ‘and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.’

Such moments are sprinkled throughout the films, such as this one from the Extended Edition of The Return of the King, when Samwise sees a star peeping through the clouds above Mordor:

Mr. Frodo, look. There is light and beauty up there that no shadow can touch.

Book readers will recognize this as an adaptation of this passage:

Far above the Ephel Dúath in the West the night-sky was still dim and pale. There, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach.

Despite Christopher Tolkien’s misgivings, it seems to me that the films did not only introduce multitudes to the stories of J.R.R. Tolkien, but at least to some extent, to his philosophy as well. Surely Jackson could have made the philosophical element more central to the films, but it is not fair to say that he reduced its impact to nothing.

In the Same Tale Still

At the time of his interview, Christopher Tolkien was understandably not very popular with fans of the films. Now he has become curiously popular with some fans of the films who nevertheless view Amazon Studios’ upcoming Second Age adaptation as an affront to the Tolkien legacy. Some even claim that Amazon waited until Christopher Tolkien’s death to make a deal with the Tolkien Estate, which is manifestly not true. The Tolkien Estate shopped around the television rights to various studios before settling on Amazon in November of 2017, the deal seems to have been finalized about six months later in May of 2018, and Christopher Tolkien died in January of 2020, shortly before filming on the series began. Christopher Tolkien was likely not the main driver behind the deal, but he was undoubtedly well aware of it, and did not prevent it from happening.

There is understandably a great deal of concern about what Amazon is attempting to do. Many commenters expressed skepticism when they thought Amazon was going to “remake” the films (as if the films weren’t themselves adaptations of a book). Since the premise of The Rings of Power has become more well known, many commenters have expressed concern that there is not enough “canon” material to use for the show, and the writers will have to make much up. That is a valid concern, but that concern springs directly from the Tolkien Estate’s decision to sell the rights to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings (and not The Silmarillion), and the decision not to re-adapt either The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. No matter whether Netflix, HBO, or some other streaming service had obtained the rights, they would have been faced with the same choice: “remake” the beloved Peter Jackson films or tell some other story that Tolkien never turned into a finished novel. Likewise, once Amazon decided to make their story a prequel, no matter whether they had ultimately settled on a story of young Aragorn, Gimli, the Angmar War, or the Second Age, they were always going to be faced with the necessity of inventing new storylines, characters, and dialog. Not that Peter Jackson and his crew were not faced with the same challenge, though to a smaller extent, when producing the films, or even Christopher Tolkien and Guy Gavriel Kay when finishing The Silmarillion.

Since I first became aware of this show, and that it was going to take place largely in the Second Age, my concern has not been that the Amazon showrunners and writers would need to make up new material. That was always obvious to me. My principal concern was rather how well the new material would fit with what Tolkien had written: it’s Tolkienianness, you might say. Of course, that’s a rather subjective quality, but the showrunners at least ought to have a good idea of what the thing is all about. For years we had very little idea if they did, in fact, know what the Second Age is all about, or even if they were fans of J.R.R. Tolkien. Then, when a select group of influential Tolkien fans was invited to London to meet the showrunners J.D. Payne and Patrick McKay, it was this, more than anything else, that impressed them. When asked what themes the show would touch upon, one of the themes the showrunners mentioned was “fear of death and a desire to live forever”. Answers to other questions revealed that the showrunners had given much thought to what Tolkien had written about the Second Age, and had given consideration to things that even many Tolkien fans had not given much thought to, such as characters using poetic diction even when they’re ostensibly speaking prose. Whether or not one agrees that their additions to the story of the Second Age are properly Tolkienian, I see no evidence that their work is not motivated by a deep love for Tolkien’s works.

A Light in Dark Places

When I ask myself what I most want from the show, I realize that it is not dotting all the i‘s and crossing all the t‘s of lore, though that is always a plus. It is also not perfect consistency and verisimilitude in the names of characters and places, though again that is always a plus. What I most want from the show after all is a story that delves into the principal themes of the Second Age with subtlety and care, and that expresses a Tolkienian philosophy without polemic. My hope is that, among the action, the panoramic views, the drama, the horror, and so on, there will also be numerous quiet moments of truth, which a series can explore more fully than a film, or even a hexalogy of films. This is the great potential of this show, and based on what the showrunners have said so far, I am encouraged that this may be the case.

No Comments