What is Philology? – Part I: Traditional Philology

Most fans of J.R.R. Tolkien’s works are probably aware that Tolkien was a professor. Many of them have likely also heard that he was a philologist—a self-described philologist, even—and that philology was a major influence in the development of Tolkien’s legendarium. But what is a philologist? What does a philologist do? Answering that question is somewhat involved.

One of the difficulties in answering that question is that the word “philology” has at least two rather distinct meanings. For lack of better terminology, I will refer to these two types of philology as traditional philology and comparative philology. J.R.R. Tolkien was a philologist in both senses of the word, although I would argue that he was more influential as a traditional philologist than as a comparative philologist. In this article I will discuss what the word “philology” has meant throughout much of history, and still means today in some academic contexts. In a subsequent article I will discuss what the word “philology” (sometimes specified as “comparative philology”) has come to mean in the past two hundred or so years. For now my purpose is mainly to explain how these terms are used, and not so much how they apply to Tolkien’s academic career. However, I will attempt to demonstrate to some degree how Tolkien’s academic activities fit these definitions of “philology”.

Explaining Tolkien

J.R.R. Tolkien composed most of his works of fiction in a language academics refer to as “Modern English”. Anyone who is reading this article is reading an example of Modern English. (Unless, of course, you are reading a translation of this article. But the original was written in Modern English.) One might think that, for those who know Modern English—particularly native speakers thereof—understanding Tolkien’s works would present no problems. Most of the time, perhaps, this is true. However, sometimes one runs into difficulties, and as more time passes since Tolkien’s day, the average reader will only run into more difficulties.

Modern Conveyances in the Works of Tolkien

Consider the following three quotations from various literary works by J.R.R. Tolkien:

Out flew a red-golden dragon – not life-size, but terribly life-like: fire came from his jaws, his eyes glared down; there was a roar, and he whizzed three times over the heads of the crowd. They all ducked, and many fell flat on their faces. The dragon passed like an express train, turned a somersault, and burst over Bywater with a deafening explosion.

—The Lord of the Rings Book I, Chapter 1: “A Long-Expected Party” (LR 1.01.049)

Legolas and Gimli were to ride again together in the company of Aragorn and Gandalf, who went in the van with the Dúnedain and the sons of Elrond. But Merry to his shame was not to go with them.

—The Lord of the Rings Book V, Chapter 10: “The Black Gate Opens” (LR 5.10.002)

But Ulmo fares at the rear in his fishy car and trumpets loudly for the discomfiture of Ossë and the rescue of the Shoreland Elves.

—The History of Middle-earth, Volume I: The Book of Lost Tales, Chapter V: “The Coming of the Elves and the Making of Kôr”

Tolkien’s legendarium, as vast an area as it covers in time and space, is generally held to take place in a set of societies that are at a level of technological development roughly equivalent to that of Medieval Europe. How, then, are we to explain the apparent references to modern (post-Industrial Revolution) conveyances in the above and similar passages from Tolkien’s works? (Especially given the conceit that they are actual translations from somewhat contemporary sources.) Here it will be necessary to consider each case separately.

In the case of the “express train”, I don’t believe there is a good way to explain it away, other than to recognize that it occurs in the first chapter of The Lord of the Rings, which was written as a sequel to The Hobbit. Tolkien developed The Hobbit as a story to tell his children. At first its setting was vague, but clearly somewhat modern. Bilbo, the protagonist of The Hobbit, drinks tea, smokes a pipe, and has a clock on his mantel. Later, as the story goes along, its setting becomes more clearly medieval, and Tolkien adds in references to his legendarium. Nevertheless, when he began writing what became The Lord of the Rings, at first he was still writing it very much in the mode of The Hobbit. Although perhaps one could try to explain the term “express train” as referring to something other than a locomotive, the most rational explanation of its existence is that it’s an example of the modern author peeking through the narration.

The case of the “van” is more relevant to my purposes, however. It’s a word Tolkien uses several times in The Lord of the Rings, and a couple of times in The Silmarillion as well. To most contemporary speakers of English, the term suggests a type of motor vehicle with a boxy shape and a large, enclosed rear area. Often it is used for transporting cargo, and has no side windows behind the cabin, but there are also passenger vans with windows all around. The word is a shortening of “caravan”, which can also mean a group of people traveling together for safety. The word is from Persian kârvân, Middle Persian kārawān, and may derive from a Proto-Indo-European root meaning “army” (see Proto-Celtic *koryos and Proto-Germanic *harjaz). However, this is almost certainly not the sense of the word which Tolkien intended.

There is another meaning of “van”, which is also shortened—not from “caravan”, but rather from “vanguard”. The vanguard is the front of a military formation, as opposed to the rearguard. The word comes from Old French avant-garde, with avant deriving from Latin ab ante (“from in front of”). The term “van” is often seen in the same context with the term “rear”. Those who are versed in the history of the Royal Navy will be aware that conventionally the rank of Vice Admiral was given to the Admiral of the Van, and that the lesser rank of Rear Admiral was, of course, given to the Admiral of the Rear of a naval squadron. The Admiral (not Vice or Rear) commanded the center of the squadron.

The meaning of the passage, then is clear: Gandalf, Aragorn, Legolas, Gimli, the sons of Elrond, and the Dúnedain all went to the head (or forefront) of the company that marched to Mordor to engage the forces of Sauron, but Merry (being wounded) was not permitted to go with them.

Ulmo’s “car” is a similar case. Contemporary English-speakers associate the word with an automobile. Many may be unaware of how old the word actually is. It is from the Latin word carrus, which referred to a wagon. Latin borrowed it from Gaulish *karros, which would have had the same form in Proto-Celtic. In fact, Latin already had a cognate word, currus, which could refer to either a wagon or a chariot. In the 19th century the word “car” tended to be used poetically to refer to a chariot. However, with the invention of the automobile, the word came to be the colloquial term used to refer to the new invention. There are other kinds of “cars”: railroad cars, trolley cars, tram cars, or airship cars (gondolas). However, the term as used today almost always refers to an automobile.

How Tolkien used the term in The Book of Lost Tales, however, is undoubtedly different. Presumably Ulmo’s car is some type of sea-chariot, drawn by sea creatures.

Sauron and Shelob

For all I know, the above clarifications may be as yet unnecessary. Contemporary English-speakers may intuitively sense that Tolkien did not use the terms “van” and “car” in the same way as they ordinarily understand them. The following example, however, is one that I know has caused misunderstanding:

And Orcs, they were useful slaves, but he had them in plenty. If now and again Shelob caught them to stay her appetite, she was welcome: he could spare them. And sometimes as a man may cast a dainty to his cat (his cat he calls her, but she owns him not) Sauron would send her prisoners that he had no better uses for: he would have them driven to her hole, and report brought back to him of the play she made.

—The Lord of the Rings Book IV, Chapter 9: “Shelob’s Lair” (LR 4.09.057)

Why would Tolkien need to explicitly tell us that Shelob didn’t own Sauron, when the phrase his cat seems to imply that the ownership was the other way around? To many speakers of Modern English, what this passage seems to be telling us may be that Sauron owns Shelob, but Shelob doesn’t own Sauron. One suggestion has been made that people don’t own cats; cats own people. Therefore, if Shelob doesn’t own Sauron, it means she has no relationship with him. This explanation approaches the truth, but in order to fully understand what Tolkien meant, one needs to understand a meaning of the verb “to own” that has largely fallen out of use. Among its rather many meanings, it may mean “to recognize” or “to acknowledge” someone’s authority. In this sense, vassals may “own” a lord, subjects may “own” a king, and worshippers may “own” the deity they worship. Using this sense, the passage above becomes easily understandable: Sauron sees Shelob as his pet, but she doesn’t acknowledge him as her master.

Traditional Philology

What I have just done is an example of “philology”, as the term has been used for much of its history. Philology is not just about etymology, however. I could have discussed how Tolkien’s experiences in the First World War may have affected such elements of his works as the Dead Marshes or the winged steeds of the Nazgûl, or how early medieval customs of ring-giving might have informed the relationship between Sauron and the other bearers of the Rings of Power. In addition to linguistics, philology may draw from varied subjects such as history, anthropology, archaeology, paleography (the study of ancient writing), codicology (the study of manuscripts), geography, law, religion, and so on. How does philology differ from literary criticism, then?

The Etymology of Philology

The meaning of the word “philology” started out very broad, and has gotten successively narrower. Its original meaning is fairly transparent. The Greek adjective (and later noun) philologos is composed of philo- (“loving”) and logos (“words”). A philologist, then, is fond of words—not necessarily individual words, as an etymologist, lexicographer, or onomatologist/onomastician deals with, but speech, discourse, language. Originally philologos could just refer to someone who was talkative, or who loved discussion and debate. However, it soon came to mean someone who was fond of learning and literature. The related noun philologia could be a synonym for “scholarship” at its broadest. As it passed from Greek to Latin, it became increasingly identified with love for and study of literature, in particular, and it has had much this sense ever since.

A Guide to a Vanished Realm

“I have read erudite tablets in obscure Sumerian and in an Akkadian that is hard to make sense of, I have studied stone inscriptions from before the Flood that are cryptic, impenetrable, and confused.”

—Assurbanipal, Emperor of Assyria (translation by Sophus Helle)

I said “much this sense”, but there is, in the traditional meaning of the Latin words philologus and philologia, as they have existed for the past two millennia or so, an important shade of distinction from the common lover or critic of literature. In his Introduction to a 1988 conference on the question “What is Philology?”, medievalist Jan Ziolkowski makes reference to an “old proverb” that says, “To read and not to understand is to disregard.” A philologist is one who is not content to disregard a work of literature merely because it is old, and hence likely also difficult to understand. Indeed, to a philologist, the fact that a work is old is often an attraction, and that it is difficult to understand is a challenge to be accepted. Curiosity, particularly about the past, is the driving force of the philologist.

The past, as they say, is a foreign country. Traditionally, works of literature have been our main ports of entry allowing us to visit those vanished realms. However, in all but the most recent cases there are no native guides left to help us interpret what we are seeing. That is the job that falls to the philologist. Philologists serve as our guides to the vanished realms of the past, reconstituting them from the texts that have come down to us. Each text is a product of the time and place in which it was composed or set down. The more time passes since then, the more changes accrue to the language, culture, customs, technology, political institutions, religion, and even perhaps the basic philosophical outlook on life. The philologist’s aim is to understand the texts as they were meant to be understood at the time and in the place in which they were written.

Philological Traditions

Of course, writing has been a worldwide phenomenon for several thousand years, and consequently so has philology. So far I have mainly been concerned with what is called “Classical philology”—the interpretation of ancient Latin and Greek texts. At first I was going to use the term “classical philology” for the type of philology I am discussing in this article. However, because the term (at least when capitalized) is associated specifically with ancient Greek and Latin literature, I decided to use “traditional philology” instead. And there are different traditions of philology. There is also Arabic philology, Hebrew philology, and Chinese philology. Chinese philology, at least, arose outside the entire tradition of Western philology.

The word “philologie” was first attested in the English language in the late 14th century, at which time no one would have used the term “Medieval philology”. However, in recent centuries philology has specialized into various fields, including Medieval philology, Romance philology, Germanic philology, Slavic philology, and so on, in addition to Classical philology. Likewise, modern philologists have their own specialties of time and place.

Tolkien and Traditional Philology

J.R.R. Tolkien, of course, specialized in Medieval English philology (in texts written in Old and Middle English), although his first exposure to the subject in formal education was to Classical philology. Although Tolkien did rather poorly overall as a student of the Classics, it was a paper he wrote in Greek philology that convinced his advisers of his abilities. They encouraged him to switch to the English department, where at the time there was more interest in philology.

As a professor at the University of Leeds, Tolkien and his colleague E.V. Gordon successfully promoted philology in an English department that had previously been wholly devoted to modern literature. After he returned to Oxford, however, Tolkien was dismayed to see the English department there fracturing along the lines of Language and Literature. Those who joined the English department to study literature tended to resent any requirement that they also study the workings of language, or historical literature not in modern translation. Nevertheless, Tolkien was able to remain a philologist within the English department until his retirement in 1959.

The tension between literature and language, however, was not quite as much with traditional philology—as I have described it in this article—as it was with a more recent sense of the word “philology”—one that I will discuss in the sequel to this article. Perhaps it was inevitable that this tension (and increasing specialization) led to the creation of a new field of study: that of linguistics.

Tolkien’s Academic Contributions

Most of Tolkien’s academic work may be classified as traditional philology, or at least as in support of traditional philology. Comparative philology may also be considered as being in support of traditional philology; however I will consider it separately in the following article. Among these activities are the creation of or contribution to dictionaries (lexicography), the etymology of specific words and phrases, the editing (and sometimes translation) of texts for modern readers in “student editions” or “critical editions”, together with explanatory notes and commentary, and the writing of standalone essays explaining antiquated texts to a modern audience. Below I will attempt to provide a more-or-less exhaustive list of Tolkien’s academic contributions in these areas, to the extent that I am aware of them. However, as this article is already long enough, I will not elaborate on more than one or two examples of each type.

Lexicography

Tolkien’s contributions to lexicography occurred mostly at the beginning of his career. After receiving his degree in English language, and after completing his military service in the First World War, Tolkien’s first job was as an assistant for the Oxford English Dictionary. There he compiled etymologies for words beginning with the letter “w”.

Around the same time, Tolkien was tasked with compiling the glossary to his former tutor, Kenneth Sisam’s Fourteenth Century Verse & Prose. Unfortunately, he found himself busy, especially after becoming a Reader in English language at the University of Leeds, and his glossary was not quite ready when Sisam’s book was published in 1921. Tolkien’s glossary was published in 1922 as a standalone book, A Middle English Vocabulary, becoming Tolkien’s first published book. Later editions of Sisam’s book included Tolkien’s glossary.

Etymology

In addition to compiling etymologies for dictionaries or glossaries, Tolkien sometimes wrote essays explaining individual words or phrases. Often these words or phrases were from specific texts he was editing, but sometimes they had other motivations. Among these essays are the following:

- “The Devil’s Coach-Horses” (1925: ME eaueres, “draught horses”, not to be confused with eoueres, “boars”)

- “The Name ‘Nodens’” (1932: Lat. < Brit. Nodens, the name of a deity)

- “Sigelwara Land” (1932 and 1934: OE sigelhearwan and sigelwaras, glossed as “Ethiopians”, but apparently originally mythological creatures)

- “The Name Coventry” (1945: from OE Cofan-treo, “Cofa’s tree”)

- “Ofermod” (1953: OE ofermōd, “overweening pride”)

- “Middle English ‘Losenger’” (also 1953: ME losenger, “flatterer”, via OF, but apparently originally from OE, meaning “liar” or “slanderer”).

“The Name Coventry” was not published in any philological journal, but rather as a letter to the editor of The Catholic Herald. Tolkien had apparently been annoyed by an article in the periodical claiming that the name “Coventry” was derived from the word “convent”.

The motivation for “The Name ‘Nodens’” was an archaeological excavation in Gloucestershire. Tolkien had been asked to give his opinion on certain Latin inscriptions containing forms of this name. Tolkien’s conclusion was that the name Nodens is not originally Latin, but rather is derived from the British (Celtic) name of a deity. This deity, whose name Tolkien interprets as meaning “snarer” or “hunter”, is known as Núadu in Old Irish, and as Nudd or Lludd in Welsh.

Translations and Editions

One of the principal functions of the philologist is to produce modern editions (sometimes including translations) of ancient or medieval texts, together with notes, commentary, and glossaries. Tolkien spent a good part of his career engaged in this type of work, although his output was not quite as great as his university colleagues would have liked. Among the text editions to which Tolkien contributed were:

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1925, with E.V. Gordon: a Middle English poem.)

- The Reeve’s Tale (1939: a tale from the Middle English Canterbury Tales, and part of the much larger “Clarendon Chaucer” which Tolkien was working on, but never completed.)

- Sir Orfeo (1944, anonymous, but most likely Tolkien’s work: a Middle English poem.)

- Pearl (1953, edited by E.V. Gordon, but published posthumously by his widow, I.L. Gordon: a Middle English poem.)

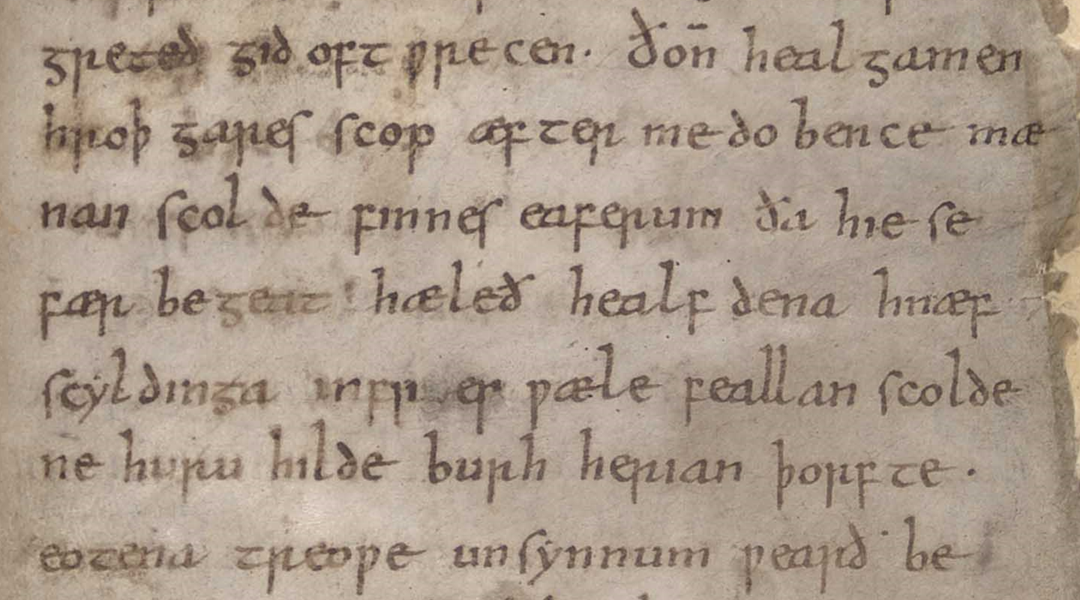

- The Seafarer (1960, edited by I.L. Gordon, initial work begun by E.V. Gordon: an Old English poem.)

- Ancrene Wisse: The English Text of the Ancrene Riwle (1962, with N.R. Ker: a Middle English religious text.)

- The Jerusalem Bible (1966: Tolkien contributed to the translation of the Hebrew books of Jonah and Job.)

Translations and other texts that have been published posthumously include:

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo (1975, edited by Christopher Tolkien: verse translations of the Middle English poems.)

- Exodus (1982, edited by Joan Turville-Petre: a prose translation and edition of the Old English poem.)

- Finn and Hengest (also 1982, edited by Alan Bliss: commentary on the Old English poem fragment called The Fight at Finnesburg and the “Finn Episode” from Beowulf, with a prose translation of the latter.)

- Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell (2014, edited by Christopher Tolkien: a prose translation and commentary on the Old English poem Beowulf.)

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1925) was perhaps Tolkien’s most widely read academic publication—at least, during his lifetime. It was in use for over forty years (going through eight impressions), before a Second Edition (edited by Norman Davis) was published in 1967. Tolkien collaborated with E.V. Gordon on the edition, with Tolkien editing the text and providing the glossary, and Gordon providing most of the notes.

Essays and Lectures

In addition to producing modern editions of ancient and medieval texts, philologists also write essays and deliver lectures on various topics related to the texts they work with. Outside of his works of fiction, J.R.R. Tolkien is perhaps best known for such essays. Among his essays and lectures are:

- “Ancrene Wisse and Hali Meiðhad” (1929)

- “Chaucer as a Philologist: The Reeve’s Tale” (1934)

- “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” (1936)

- “On Fairy-Stories” (1939)

- “Beorhtnoth’s Death” and “Ofermod” (1953)

- “English and Welsh” (1955).

By far, Tolkien’s most famous essay is “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”, first delivered as a lecture to the British Academy. It can be understood, for the most part, by a general audience. In this essay, Tolkien lamented the contemporary state of Beowulf criticism. Various scholars had proposed that the Old English poem was an amalgamation of several different stories rather than a singular work, and that idea was still quite influential. There was also a tendency to lament the main story of the poem, which dealt with the hero Beowulf’s fight with three monsters—regarded as overly fantastic or childish by some scholars. Instead, many scholars scrutinized the poem for potential references to historical figures, peoples, and events.

Tolkien argued that Beowulf was composed by a single poet, a Christian, though something of an antiquarian of the heathen past. He also argued that the monsters were essential to the story and that it would be a lesser work without them. Finally, the numerous references in the poem are incidental to the story, and the fact that in many cases we know little about the people or events being referred to only heightens the poem’s effect as being a sort of elegy for a past age.

Defining “Philology”

Dictionary definitions of “philology” tend to be broad and vague. Perhaps due to dissatisfaction with these dictionary definitions, there have been numerous attempts to define “philology” over the years. Although I believe this article may itself serve as a relatively brief definition of the word, perhaps a briefer, dictionary-style definition may be in order:

The study of antiquated texts in the contexts (linguistic, cultural, political, religious, etc.) in which they were produced, for the purpose of explaining them to an audience existing in a different (i.e., more modern) context.

My definition may have deficiencies of its own, but I believe it does capture the essence of the word as it is commonly used.

Another way to define “philology” may be by its outputs. Perhaps the principal output of traditional philology is a modern edition of a text, with notes and commentary, perhaps a glossary, and a translation into a modern language, if necessary. This then allows non-philologist historians, anthropologists, folklorists, literary critics, and so on to discuss the text intelligently without needing to be philologists themselves. An example of such an edition is Frederick Klaeber’s Beowulf and the Fight at Finnsburg (1922, 4th Edition 2008), which is considered to be the standard edition of the poem Beowulf.

A common thread in my discussion of philology so far is the text. A text may be a work of what we call “literature”: a poem such as The Iliad or Beowulf, a novel such as Apollonius of Tyre, or a philosophical work such as On the Consolation of Philosophy. However, for the purposes of philology, a text may really be anything that is written in language that impedes the understanding of most contemporary people—whether it be a chronicle, a legal text, a will, a memorial inscription, or whatever.

There is another shade of meaning to the word “philology”—one that is not concerned with individual texts, but rather with commonalities that may be found in different texts. This shade of meaning is no more than about two or three hundred years old. It is the type of philology that is sometimes, but not always, specified as “comparative philology”. That is the subject for the second part of this article.

No Comments