J.R.R. Tolkien: Professor of Anglo-Saxon

The Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon shall lecture and give instruction in the Anglo-Saxon Language and Literature, and may from time to time lecture and give instruction in the other Old Germanic Languages, especially Icelandic.

—Council Regulations 24 of 2002 (amended 2012): Academic and Other Posts, University of Oxford

Those who know anything about the life of J.R.R. Tolkien know that he is strongly associated with Oxford University. In some ways this association was inevitable. Tolkien grew up in the West Midlands of England, and attended Oxford University as a student, receiving his degree in English Language and Literature in 1915. He also worked as a tutor, and as a lexicographer on the Oxford English Dictionary after the First World War.

In 1920, however, Tolkien began working as a Reader in English Language at the University of Leeds, eventually being appointed a Professor of English Language on July 16, 1924. So things might have remained, and Tolkien—assuming he had still become a famous author—might have become more associated with Leeds than with Oxford. However, Tolkien’s circumstances changed yet again when W.A. Craigie resigned as the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon.

Note: For well over a century, scholarly practice has favored the use of the term “Old English” when referring to the West Germanic language varieties spoken in England after the Roman withdrawal and before the Norman Conquest. “Anglo-Saxon” has remained the term commonly used to refer to the speakers of Old English, their history, culture, and so on.

Although I typically follow conventional practice in this regard, things were considerably less settled in Tolkien’s day, and particularly in the century before his scholarly career began. Because of the historical nature of this article, the term “Anglo-Saxon” is often used below to refer to the language now commonly known as “Old English”, as well as to people, culture, literature, and so on. I hope that this usage will cause no confusion.

William Craigie

Sir William Alexander Craigie was born in Dundee, Scotland, the son of a gardener. His native language was Scots (usually considered a dialect of English), but from an early age he learned Scottish Gaelic (a Celtic language) from his grandfather and his older brother. He read literature in his native Scots, and began his training as a lexicographer by adding notes to the margins of John Jamieson’s Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language. He studied Classics and Philosophy at St. Andrews, as well as German, French, Danish, and Icelandic. Upon graduation, he continued his post-graduate career at Oxford, where he studied the Scandinavian and Celtic languages, as well as Classical (Latin and Greek) literature. After finishing at Oxford, he visited the University of Copenhagen to study the medieval Scandinavian languages.

Craigie returned to St. Andrews, where he served as Assistant to Alexander Roberts, Professor of Latin. He published various works, including editions of Robert Burn’s poems and collections of Scandinavian folklore. He contributed translations of Scandinavian folktales to Andrew Lang’s famous books of fairy tales, which Tolkien enjoyed as a child. (Although Lang published Tolkien’s favorite story of Sigurd before he began his collaboration with Craigie.) Craigie also taught Latin to the eminent Scottish historian and antiquarian, David Hay Fleming.

In 1897, the editorial board of the Philological Society’s “New English Dictionary” (what would become known as the Oxford English Dictionary) invited Craigie to join them as a third editor on a trial basis. Unfortunately, his appointment had been made without consulting the Chief Editor, James Murray, and the two clashed at first. Craigie proved himself a skilled and productive lexicographer, however, and was appointed an independent editor of the dictionary in 1901.

Craigie worked at Oxford University while he was with the dictionary. He was appointed Taylorian lecturer in Scandinavian languages in 1904, and taught J.R.R. Tolkien Old Icelandic during his undergraduate career as a student of English Language and Literature between 1913 and 1915. In 1916, as Tolkien was preparing to go to war, W.A. Craigie was appointed the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon, with the stipulation that he would continue to be able to lecture on Old Icelandic.

Despite his work as a professor, W.A. Craigie continued to devote time to the Oxford English Dictionary. He was ultimately responsible as editor for roughly one-fifth of its contents, including the letters N, Q, R, Si-Sq, U, V, and Wo-Wy. At Oxford Craigie had mingled with professors and students from across the English-speaking world, and he became convinced that the Oxford English Dictionary, as broad as its scope was, was still too narrow to account for the diversity of English usage worldwide. Instead of seeking to add to the size of the OED, Craigie proposed a family of dictionaries, covering different time periods (Old and Middle English) and different locations (Scotland and North America).

In 1925, the University of Chicago invited Craigie to become a Professor of English there, where he also began work on A Dictionary of American English on Historical Principles (DAE), published in four volumes between 1933 and 1944. At the same time, he began working on his Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue (DOST), which was published in twelve volumes between 1931 and 2002. Craigie only lived to see the first two volumes published by the time of his death in 1957. Soon after it was completed, the DOST was digitized and published online, along with the Scottish National Dictionary (SND). In 1936, Craigie retired from the University of Chicago and returned to live near Oxford. Despite his official retirement, however, he continued work on the DOST, and even did some work on a supplement to the OED.

Rawlinson and Bosworth

Established in 1795, the professorship that Craigie resigned from was originally called the Rawlinsonian Professorship of Anglo-Saxon. Upon Craigie’s appointment in 1916, however, it was renamed the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon.

Richard Rawlinson

The Professorship was originally named after Richard Rawlinson (1690-1755), a clergyman and antiquarian who collected numerous ancient books and manuscripts. He had intended to bequeath his collection to the Society of Antiquaries, but due to disagreements with the Society he chose to bequeath his collection to the Bodleian Library in Oxford instead. He also gave funding to Oxford University to establish a professorship of Anglo-Saxon. Arguably a professorship of Anglo-Saxon should be named after the great scholar George Hickes (1642-1715), but it was Rawlinson who provided the funds to establish the professorship.

Joseph Bosworth

Joseph Bosworth (1788-1876) was the most notable Rawlinsonian Professor of Anglo-Saxon before his name was added to the professorship. Born in Derbyshire, Bosworth attended Repton School. However, he dropped out and did not go on to the university. Nevertheless, somehow he became proficient in various European languages, including Old English. One hypothesis is that he worked for the noted historian Sharon Turner, author of History of the Anglo-Saxons.

Despite his lack of a formal education, Bosworth entered a career in the clergy. Finally, in 1822, he was awarded an M.A. by the University of Aberdeen. The following year, he published Elements of Anglo-Saxon Grammar. His aim was to describe the grammar of Old English on its own terms, without trying to fit it into the paradigms of Latin grammar. The same year, he entered Cambridge University.

Bosworth is best known for A Dictionary of the Anglo-Saxon Language, published in 1838. Thomas Northcote Toller, professor of English language at the University of Manchester, published an updated edition of Bosworth’s dictionary in 1889, titled An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, with a supplement in 1921. The so-called “Bosworth-Toller” dictionary is notable for its comprehensiveness, and is possibly the most influential dictionary of Old English. The Dictionary of Old English (DOE), published by the University of Toronto, may eclipse it once it is complete. However, despite its age, the Bosworth-Toller dictionary may still remain the go-to reference for students of Old English, as it has the advantage of being in the public domain.

In 1858, Joseph Bosworth was appointed Rawlinsonian Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford. Nevertheless, as a former Cambridge student, he also gave an endowment to the University of Cambridge to establish the Elrington and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon. In 1916, the Rawlinsonian professorship was renamed to the “Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon”, and since then Bosworth has had his name on the Anglo-Saxon professorship of both universities.

Tolkien’s Letter

The vacancy occasioned by Craigie’s resignation was an opportunity Tolkien could not pass up. On June 27, 1925, he wrote a letter of application to the electors of the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon (Letter 7, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien). (Although the letter was dated June 27, the application itself was dated June 25.) In his letter, Tolkien mentioned his undergraduate studies at Oxford, in Classical Moderations with a specialization in Greek Philology, and later in English with a specialization in Old Icelandic. He also mentioned his brief employment there, working on the Oxford English Dictionary and as a tutor, after the war. He also described his role in expanding the study of English language at the University of Leeds School of English Studies.

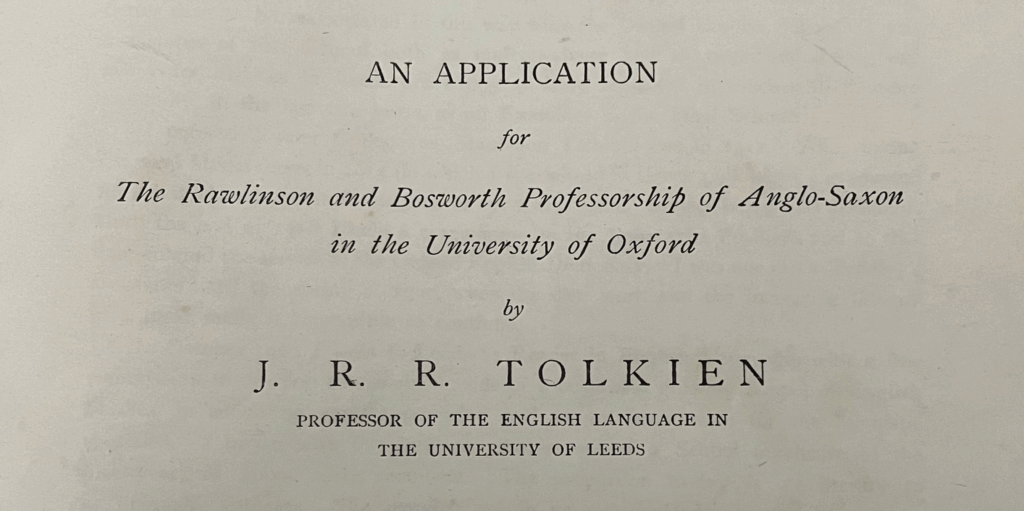

The cover page of Tolkien’s application, as held in the Papers of Charles Talbut Onions, National Library of Australia.

At the time he arrived at Leeds in 1920, the school was just beginning to expand from a focus solely on literature. Tolkien took the first five linguistics students out of sixty total students in the School of English Studies. By the time Tolkien wrote his letter of application in 1925, twenty of the school’s 63 students were linguistics students. The topics the students studied included the history of English; the philology of the Germanic languages, of Old English, and of Middle English; Old English heroic verse; various Old and Middle English texts; Gothic; Old Icelandic; and Medieval Welsh. Tolkien noted that he had taught each of the courses on the syllabus himself, from time to time. Tolkien also noted that the University of Leeds had come to develop a specialty in Old Icelandic, and that a Viking Club had been formed for the past and present students in the subject.

Tolkien appended a note regarding his research and publications to the letter (not included in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien), explaining that his duties of teaching and administration had prevented him from publishing more frequently. Among his publications, he could point to A Middle English Vocabulary (1922), which had originally been intended as a glossary to Kenneth Sisam’s Fourteenth Century Verse & Prose (1921), but was not completed in time. More notably, Tolkien had recently published an edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1925), together with his colleague at Leeds, E.V. Gordon. In addition, Tolkien had been writing yearly reviews of philological publications for The Year’s Work in English Studies, the first of which (for 1923) had been published at the beginning of 1925. Other publications listed by Tolkien included Some Contributions to Middle English Lexicography (April 1925) and The Devil’s Coach-horses (July 1925, an etymology of the Middle English word eaueres), both published in the Review of English Studies. Finally, a paper titled The Second Weak Conjugation in the Ancren Riwle and the Katherine-Group was promised to be in a “forthcoming” volume of Essays and Studies of the English Association. This last item is probably what became Ancrene Wisse and Hali Meiðhad, which was ultimately published in Volume 14 of Essays and Studies of the English Association in 1929.

Tolkien promised to work to advance amicable relations between students of both language and literature at Oxford University, and to continue his “encouragement of philological enthusiasm among the young” there. Whatever one might say of Tolkien’s academic career, there is little doubt that his influence in the latter endeavor is unmatched.

Recommendations

To support his application, Tolkien collected several testimonial letters in June of 1925. Among the academics who lent their support to his application were Joseph Wright, L.R. Farnell, George S. Gordon, Lascelles Abercrombie, Allen Mawer, and M.E. Sadler. In addition to the testimonial letters, Tolkien also submitted the letter of recommendation written by Henry Bradley to the University of Leeds, dated June 7, 1920, to support his application to the Readership of English Language there.

Henry Bradley was the second senior editor of the OED, after James Murray and before W.A. Craigie, and had been Tolkien’s employer after the war. Bradley had passed away in 1923.

Joseph Wright was Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford. He had taught Greek and Latin philology to Tolkien as a Classics student, and became his tutor when he switched to English. Born into the working class, Wright had taken night school classes to educate himself, and made money by teaching other workers. Eventually he saved up enough money to study comparative philology at the University of Heidelberg. In addition to comparative philology, he also had an interest in dialectology. He was the editor of the English Dialect Dictionary, published in six volumes between 1898 and 1905. He was also the author of various primers and grammars of ancient languages, including A Primer of the Gothic Language, which had sparked Tolkien’s interest in comparative philology.

Lewis R. Farnell had been Tolkien’s Classics tutor, and along with Joseph Wright, had encouraged him to switch to English language. Farnell was a noted authority on ancient Greek and Near Eastern religions.

George S. Gordon was the Merton Professor of English Literature at Oxford. He had previously been Professor of English Literature at the University of Leeds, and interviewed Tolkien before hiring him as a Reader in English language in 1920.

Lascelles Abercrombie was a poet and critic, and Professor of English Literature at the University of Leeds since 1922, following George S. Gordon’s move to Oxford.

Allen Mawer (who would be knighted in 1937) was the Baines Professor of the English Language at the University of Liverpool. He was strongly interested in the Scandinavian occupation of much of England in the 9th and 10th centuries (the “Danelaw”), and also in the place names of England. In 1922 he founded the English Place-Name Society, of which Tolkien had become a member in 1923. Mawer had been expected to be one of the applicants to the professorship, but he declined to apply, and supported Tolkien’s application instead.

Sir Michael E. Sadler had been master of University College, Oxford, since 1923, and was previously vice-chancellor at the University of Leeds. He was a historian by training and a prominent reformer of secondary school education in Great Britain.

Recurring themes in the testimonial letters included Tolkien’s unusual depth of philological knowledge for one so young, his unusual combination of both philological skill and literary sensibility, his ability to inspire students, and his ability to work with others.

The Election

At thirty-three years of age, Tolkien was regarded as a bit young for the Oxford professorship. His election was not a foregone conclusion. In fact, upon W.A. Craigie’s resignation, the professorship was first offered to Raymond W. Chambers of the University College of London. Chambers was known for several published works on Old English literature: Widsith: A Study in Old English Heroic Legend (1912), Beowulf: with the Finnsburg Fragment (1914, a revision of a work by A.J. Wyatt), and Beowulf: An Introduction to the Study of the Poem (1921). Tolkien himself referred to Chambers, with whom he was friends, as “the greatest of living Anglo-Saxon scholars” (Beowulf and the Critics, p. 32). Despite his apparent suitability for the role, Chambers declined the professorship when it was offered to him.

The Electors

Chambers having declined the position, the new Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon was decided by a vote of seven electors:

H.M. Chadwick, Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Cambridge. Chadwick was a philologist and a historian. Among his works was The Heroic Age (1912), which compared heroic poetry from different cultures, notably ancient Greek and Germanic epic poetry. Chadwick hypothesized that a “heroic age” was a stage in the development of civilizations in general.

R.W. Chambers, Quain Professor of English Language and Literature at the University College of London. Having turned down the professorship, he was permitted to be one of the electors. As noted above, he was a respected scholar of Anglo-Saxon literature.

Hermann G. Fiedler, Taylorian Professor of the German Language and Literature, Oxford. Fiedler was editor of The Oxford Book of German Verse (1915), and had been a German tutor to Edward, Prince of Wales, between 1912 and 1914. His former pupil would become King Edward VIII in 1936 before abdicating in the same year.

C.T. Onions, Lecturer in English, Oxford. Onions was the author of Advanced English Syntax (1904), A Shakespeare Glossary (1911), and a revision of Henry Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Reader (1922). He had been on the staff of the OED since 1895, co-editor since 1914, and upon W.A. Craigie’s departure he became the fourth and final senior editor of the first edition of the OED (not counting supplements). He later published the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1933) and The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (1966).

Rev. Charles Plummer, Fellow of Corpus Christi College. Plummer was a historian. Among his publications were a revised version (1892) of John Searle’s Two of the Saxon Chronicles Parallel; Venerabilis Baedae: Historiam Ecclesiasticam Gentis Anglorum (1896), a Latin edition of Bede’s history of Christianity in England; Vitae Sanctorum Hiberniae (1910), a collection of lives of Irish saints in Latin; and Bethada Náem nÉrenn: Lives of Irish Saints (1922), a collection of lives of Irish saints originally in Irish, with Modern English translations. Charles Plummer’s edition of Bede’s history was the first modern critical edition of the text.

Joseph Wells, Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University between 1923 and 1926. He was also Warden of Wadham College between 1913 and 1927. Wells was a Classical scholar, and a noted authority on the Greek historian Herodotus. He also authored books on the history of Oxford University.

H.C. Wyld, Merton Professor of English Language and Literature, Oxford. (There are two Merton Professors: George S. Gordon was professor of English Literature only.) Wyld was old enough to have been taught by the great English linguist and phonetician, Henry Sweet, who died in 1912. Wyld authored several books on the history of English, including The Growth of English (1907), A Short History of English (1908), and A History of Modern Colloquial English (1920). He was also the author of a book on the methods of comparative philology: The Historical Study of the Mother Tongue (1920). He would later publish The Universal Dictionary of the English Language (1932). Upon Wyld’s death in 1945, Tolkien would be elected to succeed him as the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature.

The Other Applicants

There were three applicants to the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon. R.W. Chambers, having declined the professorship (and being one of the electors), and Allen Mawers, having declined to submit an application for the professorship, were not among them. The most well-known of the applicants is, of course, J.R.R. Tolkien. His principal competitor for the position is also fairly well known: Kenneth Sisam. There was a third applicant, however, whom the electors considered for the professorship. Although not much is known about him, thanks to the Oxford University Archives, we now know his name: S.J. Crawford.

Kenneth Sisam

Born in 1887, Kenneth Sisam was over four years older than Tolkien. Like Tolkien, Sisam was born outside of England—New Zealand in Sisam’s case. Unlike Tolkien, however, Sisam did not come to live in England until 1910, as a graduate student on a Rhodes scholarship.

At Oxford Sisam served as an assistant to Arthur S. Napier, who at the time was simultaneously the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature (of which he was the first) and Rawlinsonian Professor of Anglo-Saxon. Professor Napier was in poor health, although he still managed to teach some classes. Kenneth Sisam also taught various classes to the undergraduate students. He taught historical phonology to Tolkien, and also became his tutor. Tolkien considered himself fortunate to have been Sisam’s pupil, as he taught with humor and wisdom.

Sisam completed a B.Litt. at Merton College, Oxford, in 1915. Since he was judged physically unfit for military service, he got a job working as a lexicographer on the Oxford English Dictionary. In 1922 he started work at the Oxford University Press, serving as assistant secretary until 1942, when he was appointed secretary.

Sisam had several publications at the time of his application to the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon. These included The ‘Beowulf’ manuscript (1919), Textual notes on the Old English ‘Epistola Alexandri’ (1919), An Old English translation of a letter from Wynfrith to Eadburga (A.D. 716-7) in Cotton MS. Otho C. 1 (1923), and The authenticity of certain texts in Lombard’s ‘Archaionomia,’ 1568 (1925). All were published in The Modern Language Review.

Sisam had also published a revised edition of The lay of Havelok the Dane in 1915 (formerly edited by Sir Frederic Madden in 1828, and by Walter W. Skeat in 1868). Most notably, however, Sisam was the editor of Fourteenth Century Verse & Prose (1921). This is the book for which Tolkien was tasked with writing the glossary, belatedly published as A Middle English Vocabulary in 1922. Later printings often included the glossary. The whole work (including Tolkien’s glossary) has also been reprinted by Dover Publications under the title A Middle English Reader and Vocabulary.

Sisam’s post-1925 publications included various articles, including one on Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies (1953). His published books included Studies in the History of Old English Literature (1953), a collection of essays, some being reprints and others being published for the first time; The Structure of Beowulf (1965); and The Oxford Book of Medieval English Verse (1970), co-edited with his daughter, Celia Sisam.

Samuel John Crawford

Born in 1884, S.J. Crawford was older than either Tolkien or Sisam. Much less is known about Crawford than the other candidates. He had completed a B.Litt. at St. John’s College, Oxford. He is known mostly for editions of Old English religious texts. At the time of his application, he had published Exameron Anglice; or, The Old English Hexameron (H. Grand, 1921) and The Old English Version of the Heptateuch, Aelfric’s Treatise on the Old and New Testament and his Preface to Genesis (Early English Text Society, 1922).

Later, he would publish The Gospel of Nicodemus (I.B. Hutchen, 1927) and Byrhtferth’s Manual (Early English Text Society, 1929). The former is an Old English version of an Apocryphal work, and the latter is a scientific textbook written by Byrhtferth, an Anglo-Saxon monk. At the time these works were published, Crawford was associated with University College, Southampton.

Crawford died at a relatively young age in 1931. After his death, in 1933, the Oxford University Press published Anglo-Saxon Influence on Western Christendom, 600-800. This consisted of lectures delivered by Crawford at University College in April and May of 1931.

The Vote

The seven electors met together on July 21, 1925, to decide which of the three applicants should succeed W.A. Craigie as the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon. Professor Chambers began by explaining why he had declined the professorship, though the reasons he gave are not recorded in the meeting’s minutes. Next, applications were received from the three candidates: S.J. Crawford, K. Sisam, and J.R.R. Tolkien.

According to the minutes of the meeting, there was “some discussion” of the candidates, but the arguments were not recorded. Perhaps to Tolkien’s detriment were his relative youth and the fact that, among his publications, none were related specifically to Old English. Nearly all of them focused on Middle English. On the other hand, in Tolkien’s favor were likely his success in developing the language side of the English school at Leeds, the fact that he had lectured in all of the subjects (including Old English, Old Icelandic, and other ancient Germanic languages), and the fact that the University of Leeds had already seen fit to appoint him as Professor of English Language. The electors might also have been impressed by the testimonials he was able to gather.

The contest was ultimately between Tolkien and Sisam, and it was a close vote: three electors cast their votes for Sisam, with the four remaining casting votes for Tolkien. Only one round of voting is noted, so presumably Crawford received no votes. Tolkien’s selection was announced in The Times on the next day. On July 22, 1925, J.R.R. Tolkien knew he had been selected as the new Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon.

Pembroke College, University of Oxford

(Photograph by Robin Stevens)

Tolkien as Professor of Anglo-Saxon

In order to accept his new position, Tolkien needed to resign from his professorship at Leeds. The problem was that he had not yet informed the university of his resignation, and he was required to give them a semester’s notice before resigning. Consequently, Tolkien remained in Leeds for the remainder of 1925, fulfilling his duties as a professor there. However, he also traveled to Oxford to give lectures on the weekend. Only in 1926 was Tolkien able to devote his whole scholarly efforts to his job as Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College.

Lectures and Teaching

The Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon was not a mere research position. Tolkien was expected to “lecture and give instruction in the Anglo-Saxon Language and Literature”. Much less attention has been paid to Tolkien’s teaching than to his writing of literature. Apart from the occasional student anecdote about Tolkien’s teaching style, most of the records of his teaching are probably gathering dust (figuratively speaking) in the Bodleian Library. However, an overview of the subjects Tolkien taught is contained in the article, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Formal Lecturing and Teaching at the University of Oxford, 1925-1959 (2002), by John S. Ryan.

A thorough list of the courses Tolkien taught is beyond the scope of this article, and would also be duplicative of Ryan’s work. Ryan notes that at first the courses Tolkien taught were similar to those taught by his immediate predecessors in the professorship, W.A. Craigie and A.S. Napier. In particular, there was an emphasis on Germanic philology, as well as both Continental Germanic and Anglo-Saxon heroic literature. As a professor of Anglo-Saxon, Tolkien largely ignored Middle English in his lectures, even though he did continue to publish on the subject.

In 1930, Tolkien published an essay titled “The Oxford English School” in The Oxford Magazine. His essay addressed the growing divide between students primarily interested in linguistics and those primarily interested in literature, especially modern literature. Tolkien’s proposed solution to the problem was to reform the school’s curriculum by offering multiple courses (or tracks), each with a somewhat different curriculum.

Tolkien’s suggestions were implemented in 1932, and students of English were given the choice of three courses: one focusing on Old English and other ancient Germanic languages and literature, one focusing on Middle English language and literature, and one focusing on literature until 1830, albeit with a small component devoted to the history of the English language. Although the basic idea may have been sound, the implementation left much to be desired, from the perspective of the literary student. Tolkien believed that all students of English should have some understanding of the history of the language, and there was little enthusiasm among the Oxford professors for teaching contemporary literature.

After the curriculum reform was implemented, the content of Tolkien’s lectures shifted somewhat. In particular, he narrowed his focus to the Old English language and Anglo-Saxon literature. Perhaps this was due in part to the curriculum reform, but it was also certainly due to the increasing expertise of Tolkien’s pupils and junior colleagues. Although Old Icelandic was an express part of his job description, Tolkien delegated courses on the subject to E.O.G. Turville-Petre. Likewise, although the ancient Continental Germanic languages were also part of his job description, Tolkien delegated most courses on the subject to C.L. Wrenn, apart from a few courses on Grimm’s and Verner’s Laws. Perhaps Tolkien sensed that, with the work of scholars such as Eduard Sievers and, more recently, Karl Luick, the study of Old English historical linguistics was becoming a field in its own right, and therefore merited increased attention from a professor of Anglo-Saxon.

Speeches and Publications

Although his lecturing focused mainly on Old English, the ancient Germanic languages, and their literature, Tolkien allowed himself more latitude in his speeches and publications. In 1929 he published Ancrene Wisse and Hali Meiðhad, which, to be fair, was based on work he had already begun at Leeds. In addition, he published Chaucer as a Philologist: The Reeve’s Tale in 1934. Both articles were on Middle English subjects.

Tolkien’s interests were not limited to English, or even the Germanic languages, however. In 1932 he had an article, “Appendix I: The Name ‘Nodens’”, published in Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman, and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire. It concerned a British Celtic name of a deity that had turned up in Latin inscriptions.

Tolkien did publish on the topics of the Old English language and Anglo-Saxon literature as well. He published the article Sigelwara Land in two parts in 1932 and 1934, on the topic of an Old English term—sigelwaras or sigelhearwan—that was used to translate the Latin word for Ethiopians. What was curious is that, instead of simply borrowing the Latin term, as was often done, for some reason the Anglo-Saxon scribes apparently supplied a native word that had some history behind it, and a mythological meaning.

Most notable of all, however, was the speech Tolkien delivered to the British Academy on November 25, 1936: Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics. In it he decried the contemporary state of criticism of the Old English poem Beowulf. The poem was of immense interest to antiquarians for its numerous references to legendary and historical figures and events. However, due to its focus on a hero who fights monsters, it was often not taken seriously as a work of literature.

In his speech, Tolkien argued that contemporary scholars were missing the point of the poem. Instead of lamenting it for not being what they thought it should be, they should take it for what it actually was. In particular, Tolkien argued that the poem was a meditation on life and inevitable death, and that the monsters served to elevate that theme. Replacing the monsters with human warriors would not increase the literary value of the poem, and indeed would make it seem more petty.

Tolkien delivered the speech again to the Manchester Medieval Society two weeks later, and it was printed the following year. The scholarly reaction to Tolkien’s speech was favorable, and it is no exaggeration to say that it marked a turning point in Beowulf studies. It is also, perhaps, Tolkien’s most well-known academic contribution.

Tolkien delivered several other speeches that were less directly related to the language and literature of Anglo-Saxon England. In November 1931 he delivered the lecture known as A Secret Vice to a literary society at Pembroke College, on the topic of invented languages, linguistic aesthetics, and the importance of mythology to the appeal of such languages.

Also, Tolkien was invited to give a speech about Andrew Lang at the University of St. Andrew in March of 1939. He delivered the speech, On Fairy-Stories, in which he argued that the appeal of such stories comes not from a naive belief that they are (or at least could be) true, but rather from a natural desire to create, and an appreciation for the creations of others. Such stories, then, should be judged not for their “realism”, but for their inner consistency and the ways in which they reflect the truth of the Primary World. His arguments reflect those he made earlier in his speech on Beowulf.

Extracurricular Pursuits

Tolkien may have had an ulterior motive for Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics: it doubled as a defense of what he called “fairy-stories”. Indeed, at the time he delivered his speech to the British Academy, he had completed his typescript of The Hobbit and delivered it to his publisher. It would be published in 1937, a few months after the publication of Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, and would make Tolkien an internationally-acclaimed children’s author.

Tolkien had been creating his own languages and writing poems and stories for over a decade when he became the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon. Of course, he did not stop on becoming an Oxford professor. He had abandoned The Book of Lost Tales, his first attempt at an Elven mythology, around the time he went to Leeds. However, he began writing a “Sketch of the Mythology” in 1926 as an outline of what he would later call the Quenta Silmarillion. This outline was followed in 1930 by an expanded account, which he called the Quenta Noldorinwa. This was the only version of The Silmarillion which Tolkien completed in his lifetime. All other drafts are unfinished, or of individual tales. He continued to work on The Silmarillion during the 1930s until the success of The Hobbit demanded a sequel, and he set it aside for over a decade.

It was while he was Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College that Tolkien first conceived of The Hobbit, and he was still at Pembroke College when it was published. With the success of the book, his publisher demanded anything else he could provide them with. Tolkien sent Allen & Unwin various manuscripts he had been working on. Of course, he submitted his latest unfinished version of the Quenta Silmarillion, as well as the related works, the Ainulindalë, the Ambarkanta, and The Lay of Leithian. He also submitted a story called The Lost Road, which was his first version of the story of Númenor, as well as The Fall of Númenor, in which he had begun to connect the story to his Elven mythology. In addition, he submitted the stories Roverandom, Mr. Bliss, and Farmer Giles of Ham. None of them were published at the time.

What Allen & Unwin really wanted was a sequel to The Hobbit: another story about Hobbits. Tolkien felt that the story of Bilbo Baggins was complete, but he somewhat reluctantly began working on a sequel. As he wrote, he began connecting the story of The Hobbit to the events of the Quenta Silmarillion. He had already begun connecting the story of Númenor to his mythology. And, indeed, even The Hobbit contained several references to the Silmarillion. This sequel would eventually become Tolkien’s most well-known work, with the possible exception of The Hobbit. He called it The Lord of the Rings. It took him a dozen years to complete the story. It was another five years before it was finally published, due to negotiations with publishers while working on the Appendices to the book and also a Silmarillion rewrite. While he was at Pembroke College, Tolkien completed the story through Book IV (the end of The Two Towers).

Tolkien published the short story Leaf by Niggle in 1945. Despite his avowed distaste for allegory, the story is apparently allegorical—if not an actual allegory—and reflects Tolkien’s concern that his various creations would remain unfinished in his lifetime.

Tolkien also had various poems published while he was at Pembroke College. Among them was “The Adventures of Tom Bombadil” (1934), which would eventually become the basis for an episode in The Lord of the Rings.

Merton College, University of Oxford

(Photograph by David Hallam-Jones)

Leaving Pembroke College

On January 26, 1945, Henry C. Wyld died. Wyld had been the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature, and was also one of the electors who selected the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon in 1925. Wyld’s successor was elected on June 23, 1945: J.R.R. Tolkien. After nearly twenty years as the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon, Tolkien had decided to move on.

Just as when he left Leeds for Oxford, however, Tolkien was unable to leave his old job immediately. The new Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor had not been selected, so for a year from October 1945 to October 1946 Tolkien was doing the work of both professorships. As if that were not enough, David Nichol Smith, the Merton Professor of English Literature, retired in 1946, leaving Tolkien to run the Merton English school by himself until a new professor could be selected. Fortunately the commute was not as long as that from Leeds.

Meanwhile, Tolkien had started work on The Notion Club Papers, his latest version of the story of Númenor, and had begun creating Adûnaic, the language of Númenor. All this while he was supposed to be working on The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien had too many responsibilities to attend to, and his health began to suffer after Christmas, 1945.

Tolkien abandoned his work on The Notion Club Papers. In July of 1946 he informed his publisher, Allen & Unwin, that he was putting The Lord of the Rings “before all else” (Letter 105, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien). His colleague Charles Leslie Wrenn had been chosen to succeed him in the Anglo-Saxon professorship and took over his remaining duties in October. Wrenn held the chair until 1963, when he was made Professor Emeritus. He was succeeded by Tolkien’s former pupil, Alistair Campbell, who held the professorship until his death in 1974. F.P. Wilson was elected to the Merton Professorship of English Literature in 1947, leaving Tolkien free to attend fully to his own professorial responsibilities.

As Professor of English Language and Literature at Merton College, Tolkien continued to lecture on the history of the English language. However, his duties required him to lecture on the Middle English era (“the period of Chaucer”), in particular. Tolkien then focused on Middle English literature more than Anglo-Saxon literature. It was while he was at Merton College that Tolkien published The Lord of the Rings in three volumes, in 1954 and 1955. In 1959, after fourteen years as Merton Professor of English Language and Literature, Tolkien retired from his career as an Oxford professor.

Note: Special thanks are due to David Roberts of Fellowship of Fans, and Andrew Ferguson and Phil of the Tolkien Collector’s Guide, for background on Tolkien’s application. Special thanks are due as well to Amanda Ingram, Archivist at Pembroke College, and especially to Frances Pattman, Senior Archivist at the Oxford University Archives, for background on Tolkien’s election.

Tolkien’s application is held by the National Library of Australia: “Galley proofs and other material, 1925-1958”, Papers of Charles Talbut Onions, National Library of Australia, MS 2089, (File 6) – Box 9.

The minutes of the meeting in which Tolkien was elected to the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon are held by the Bodleian Library in the Oxford University Archives: DC 9/1, “Volumes containing minutes of various meetings chaired by the Vice Chancellor, chiefly of Boards of Electors to University posts”, 1. 1898-1937.

No Comments