A War of the Rohirrim Onomasticon

“Out of these languages are made nearly all the names that appear in my legends. This gives a certain character (a cohesion, a consistency of linguistic style, and an illusion of historicity) to the nomenclature, or so I believe, that is markedly lacking in other comparable things. Not all will feel this as important as I do, since I am cursed by acute sensibility in such matters.”

—J.R.R. Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter 131 to Milton Waldman

With the imminent worldwide release of The War of the Rohirrim only two weeks away, I’ve decided to take a look at the proper names of the film. This includes all the names of people and places specifically created for the film that have been released publicly, as well as a few other names from Tolkien that could possibly turn up in the film.

The technical term for a list of proper names, usually with etymologies, is an onomasticon. (I suppose I could have also resurrected the Old English nambōc as “name-book”.) In previous articles, before the release of The Rings of Power Season One, I have covered the places and people of the Second Age. Now it is time to take a look at the people and places (but mostly people) of the story of Helm Hammerhand.

As this film is about the Rohirrim, many of these names are Old English. J.R.R. Tolkien used Old English, the historical language of the Anglo-Saxons, to represent the language of the Rohirrim, even though Rohan supposedly existed thousands of years before the Angles and Saxons settled England (which traditionally happened beginning in AD 449). Consequently, it should be a fairly straightforward matter for someone with a knowledge of Old English to invent or interpret names in the language of Rohan.

Despite this fact, I have come across purported Rohirrim names that make no sense in Old English—even some that don’t fit the phonological patterns of Old English. I won’t name names in this particular article (unless The War of the Rohirrim is an offender), except to say that, from what little I have seen so far (not actually having played the game yet), it seems to me that The Lord of the Rings Online is the Tolkien adaptation that does it the best. (I mean those whose job it is to create the content, of course; not necessarily the individual players.)

The names are one element of the film I have been anticipating the most. Now that we have some data to work with—thanks to the Visual Companion, the 2025 Calendar, and so on—I will be taking a close look at these new names, and how well I think they fit with the names Tolkien himself created. Probably there are a few names from the film that still remain unknown, but at least those of the major dramatis personae should have been released publicly by now.

[Ed: since the release of the film and supporting books, more is said on the matter of names from the film in this post from 2025]

Anglo-Saxon Names

Before looking at specific names, I think it’s worth discussing how Anglo-Saxon names work. The first point to consider is that they are in Old English. This may seem an obvious point, but in the Modern English-speaking world, most names are not English. And by that, I don’t just mean that most names contain root words that are not of “native” English origin (for our purposes, words that are attested in Old English). The names Joy, Grace, Amber, Ruby, and Lance are not “native” English words, but they have meaning to most native English speakers. However, such names are relatively rare.

Most given names used in the Modern English-speaking world have no apparent meaning to the vast majority of native speakers, and that includes such native English names as Alfred, Edward, and Edith. But, of course, it also includes many names of other origins, such as Helen (Greek), Anthony (Latin), Rachel (Hebrew), and Kevin (Irish). In contrast, the great majority of Anglo-Saxon names are composed of Old English words whose meaning contemporary Anglo-Saxons understood. Some name elements may have been archaic or poetic, but in general any contemporary name was understood.

Old English Orthography

A few notes before continuing: I follow Tolkien’s convention in using the acute accent to indicate long vowels in names from Rohan, but otherwise I use contemporary scholarly convention when writing Old English words. For example: “Théoden” when discussing the Tolkien character who was King of Rohan, but þēoden when discussing the Old English word.

Historically, different scholars have used the acute accent, the circumflex, or the macron to mark Old English long vowels: Háma; Hâma; Hāma. Since roughly the mid-20th century, the macron has been favored by scholars of Old English. I am not aware that the grave accent has ever been used by scholars to mark Old English long vowels: *Hàma. In an Old English context, the grave accent is typically only ever used to mark secondary stress on a syllable, e.g. Modern English úp·brìng·ing, where “up” has primary stress, “bring” has secondary stress, and “-ing” is unstressed. This would not apply in a word such as Háma (or Héra), where neither syllable has secondary stress.

Although the “long” vowels of Modern English are a historical development of the Old English long vowels (for the most part), they were not pronounced the same. The long vowels of Old English were metrically long. That is, they were pretty much the same as the short vowels in quality, but were pronounced for a longer period of time. For example, the difference between Old English a and ā is like that between the General American English pronunciation of “pot” /pɑt/ and the British English pronunciation of “part” /pɑːt/.

Also note that the Old English letter þ was pronounced like Modern English “th”, either as in “thorn” or as in “that”, depending on the context. It was used interchangeably with ð, unlike in Old Icelandic, where the two letters consistently had different values. I have chosen to standardize on þ here (“Æþelþrȳþ”), although I could just as well have have used ð (“Æðelðrȳð”). The Old English letter æ was pronounced like the “a” in “happy”. The letter y was pronounced like the German ü.

Types of Names

Anglo-Saxon names were generally one of four types: monothematic, dithematic, hypocoristic, or bynames.

Monothematic Names

Monothematic names consist of a single element: for example, Wulf (“wolf”) and Hild (“battle”). In Old English, monothematic names often contained only one syllable, but they could also contain two (e.g., Hengest “stallion”), or sometimes perhaps even three syllables (e.g., Hagena, of uncertain etymology). Some names consisted of a single root element plus a suffix, for example: Golding (roughly, “from gold”). Such names are still considered monothematic, since the suffix is not an independent word.

Dithematic Names

Dithematic names consist of two elements put together: for example, Wulfstān (“wolf” + “stone”), Æþelwulf (“noble” + “wolf”), Hildeþrȳþ (“battle” + “strength”), and Ælfhild (“elf” + “battle”). These elements were usually nouns, but could also be adjectives. Sometimes both elements made sense together, but it was not necessarily always the case. The modern name Roseanne is not ordinarily understood—except by baby name books—as meaning something like “rose grace”. Rather it is seen as the combination of two separate names, “Rose” and “Anne”, each with its own separate meaning. This also seems to have been the case in Anglo-Saxon England, for some dithematic names at least.

In Anglo-Saxon England, dithematic names seem to have been the most popular type of name by far. The first and second elements of a dithematic name are known as the prototheme and the deuterotheme, respectively, but I think this article has enough Greek words anyway, so I will ignore those terms for the rest of this article.

Hypocoristic Names

Hypocoristic names are nicknames formed by shortening and/or transforming the original name in certain ways. They are used to show affection, or at least familiarity. For example, the names “Liz”, “Beth”, “Lisa”, and “Lizzie” are hypocoristic forms of the name Elizabeth. The Anglo-Saxons also had hypocoristic names. For example, Wulfstān or Æþelwulf might also be known as Wulf or Wuffa. Hildeþrȳþ or Ælfhild might be known as Hild or Hille. As may be seen, it is not always possible to distinguish monothematic from hypocoristic names.

Hypocoristic names were popular throughout the Anglo-Saxon period, and some historical figures are only known by such names. A historical king of Mercia and a legendary king of the Angles before the settlement of England shared the name Offa, presumably a hypocoristic name.

Bynames

Bynames are nicknames given to people based on some trait, quality, or circumstance. Often they were used to distinguish between different people who had the same name, being a sort of precursor to modern surnames. However, they were not inherited in Anglo-Saxon times, but only applied to individuals. Bynames were usually placed after the given name, but were sometimes used in place of it.

Perhaps the most well-known Anglo-Saxon byname is that of Æþelrǣd Unrǣd, or Æthelred “the ill-advised”, a King of England who lost his kingdom to the Vikings, though he did gain the kingdom back shortly before his death. Here his byname Unrǣd is clearly a play on his given name Æþelrǣd (“noble counsel”), but most bynames did not reference the given name. His son Ēadmund had the more complimentary byname “Ironside” (Īrensīde).

The Gender of Names

Old English had three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. As a rule, if the final element of an Anglo-saxon name was a masculine or neuter noun, the name was masculine. If the final element of the name was feminine, it was usually a feminine name.

There were exceptions, however. The Old English words mund (“hand; protection”) and nōþ (“boldness”) are both feminine, but they were used as the final element of names borne by male historical figures such as Ēadmund and Byrhtnōþ. Likewise, geard (“enclosure”) was a masculine noun, and although it wasn’t much used in Anglo-Saxon names, it was popular in Continental Germanic names such as Hildegard and Irmingard, which were feminine names.

Some name elements were adjectives, such as beorht (“bright”), swīþ (“strong”), and hēah (“high”). Adjectives had no inherent grammatical gender. Nevertheless, names that end in beorht, for example, are assumed to be masculine, because those who bore such names are known to be males, in cases where their gender is known. Likewise, names that end in swīþ are assumed to be feminine for the same reason.

The actual meaning of names was significantly less important to determining their gender than was grammatical gender. Common feminine name elements included burg (“fortress”), gȳþ (“battle”), hild (“battle”), swīþ (“strong”), and þrȳþ (“strength”). Even though war was generally the province of men in Anglo-Saxon and other Germanic societies, parents apparently saw nothing odd with giving their daughters names of martial significance.

Which is not to say that all Anglo-Saxon names were warlike. Other feminine name elements included gifu (“gift”), lufu (“love”), and wynn (“joy”). Also, flǣd is often interpreted as meaning “beauty”, although this is not certain. Another suggested meaning is “birth”. In Continental Germanic feminine names, the element lind (“soft”, “tender”, or “lithe”) was rather popular, for example in Rosalind (“horse” + “lithe”) and Sieglinde (“victory” + “lithe”). In Old English these names would be Horslīþe and Sigelīþe. Although it was exclusively used as the first element in a name, mild (“gentle”) was particularly popular in feminine names. As for masculine names, although many of them were suitable for warriors, one quite common element was friþ, which means “peace”.

Names in The War of the Rohirrim

Here I will take a look at the characters and some other proper names from the film, The War of the Rohirrim, based on publicity materials and merchandise released so far. First I will look at names that Tolkien himself created. Then I will look at names created for the film and see how they compare. Where names consist of a single element, I will assume they are monothematic rather than hypocoristic, unless there is evidence to the contrary.

Names Created by Tolkien

Helm Hammerhand

Helm “Hammerhand” is the King of Rohan in the film. The name Helm is a monothematic name. It means “helmet” literally, or more figuratively “ruler” or “protection”, in Old English. The modern word “helmet” is a diminutive form of the same word, which was borrowed from Norman French. Helm also has a byname, “Hammerhand”. This is in Modern English, although it would not be too different in Old English (Hamorhand, among several possible variants).

This byname presumably refers to his great strength, but for some reason Helm is also shown in the film literally holding a hammer in his hand. (There is a statue of Helm with a hammer in the live-action films, so the literal hammer is not without precedent.) Helm’s byname should not be interpreted as a modern family surname, although I have seen articles online that talk about “Héra Hammerhand”. Unless Héra herself kills someone with one punch, this is wrong.

Hild

Hild is the sister of Helm, and his only known sibling. I haven’t seen much mention of her in relation to the film, so she may not even appear in it. Her principal importance in Tolkien’s story—and presumably the film as well—is that she is the mother of Fréaláf Hildeson. Hild is a monothematic name that means “battle”. It would also be the perfect name for Helm’s daughter if Tolkien hadn’t already used it for his sister.

Haleth

Haleth is Helm’s eldest son. His name is also monothematic, from Old English hæleþ, a poetic word meaning “hero”, “warrior”, or “man”. Not to be confused with the woman of the same name in The Silmarillion, who led one of the three Houses of the Edain in the First Age (although her character was originally a man). Also not to be confused with the character—a boy who fought at Helm’s Deep—invented for the New Line film, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers.

Háma

Háma is Helm’s second son. His is also a monothematic name. It is the Old English name for the deity known in Old Norse as Heimdallr, who guards the rainbow bridge from Miðgarðr to Ásgarðr. The name Háma is likely related to the Old English root word hām, meaning “home”. Not to be confused with Théoden’s doorward of the same name—who was not eaten by a Warg, except in the films. (Though he did die in the Battle of the Hornburg.)

Fréaláf Hildeson

Fréaláf Hildeson is Helm’s nephew, the son of his sister, Hild. This avunculate relationship—between mother-brother and sister-son—was regarded as highly significant in ancient Germanic and Celtic cultures. Fréaláf’s name is dithematic, from the Old English elements frēa, meaning “lord”, and lāf, meaning “remnant” or “heir”. He also has the byname “Hildeson”, obviously meaning “son of Hild” (Old English Hildesunu), which emphasizes his connection to the royal family.

Freca

Freca is one of Helm’s lords, who claims descent from Helm’s great-great-grandfather, King Fréawine. He is also apparently partly of Dunlending ancestry as well. Freca’s name is monothematic. It means “one who is bold” or “warrior” in Old English, but can also mean “one who is audacious” or “one who is greedy”.

Wulf

Wulf is the son of Freca. His name is monothematic. It literally means “wolf” in Old English. It was a popular masculine name, both alone and in combinations such as Æþelwulf, Gūþwulf, Wulfstān, etc. Figuratively, Wulf can mean “outlaw”, and indeed Helm declares him an enemy in Tolkien’s story, forcing him to flee to Dunland.

Saruman

The Wizard Saruman, who is already well known to many from The Lord of the Rings, is in the film. His name is dithematic, and also from Old English, presumably given him by the Rohirrim. The first element is from searu, meaning “art”, “device”, “contrivance”, “deceit”, “stratagem”, or “machine”. The second element is from mann, meaning “a person”. This is roughly the same meaning as his Sindarin name Curunír: “skilled man”, or “cunning man”.

Éowyn

Éowyn is also in the film—at least, as the voice of the story’s narrator. Her name is dithematic, from the Old English elements eoh (“horse”) and wynn (“joy”). The form of her name represents a historical sound change that is known to have occurred in Old English: the loss of medial h with compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel: Eohwyn(n) > Éowyn(n). A similar sound change occurred in later English—for example in the word “light”, which originally had a short vowel. Even more recently, in some dialects of English the loss of post-vocalic r has led to compensatory lengthening of the previous vowel: e.g., “harm” > “haam” (hām).

Beren and Beregond

Finally, although I have not seen their names mentioned in connection with the film—and they may not even be mentioned in the film itself—I think it is worth noting that Beren is Steward of Gondor at this time, and Beregond is his son. These are not to be confused with the Beren of the First Age who fell in love with Lúthien Tinúviel, or the Minas Tirith guard named Beregond who befriended Pippin. Their names are Sindarin, meaning “bold” and “bold stone”, respectively.

Names Created for the Film

Héra

Of the names created for the film, Héra’s is by far the most prominent, and hence the most controversial. Héra is the daughter of Helm, and the one who sets the whole story in motion, albeit passively in Tolkien’s account. It is Freca’s proposal to have his son Wulf marry her, and Helm’s response to the proposal, that leads to everything that happens thereafter.

Helm’s daughter remains unnamed in Tolkien’s brief account, but for a feature-length film about the story, it is unthinkable that she remain nameless. The writers’ and producers’ solution, however, has not been universally accepted. One common complaint is that “Hera” is the name of a Greek goddess (etymology uncertain, but possibly related to “hero”). This is not necessarily an issue. There are girls and women in Central Asia who have the name “Nazgul”, and in those cases the similarity with the name of Tolkien’s Ringwraiths is a mere coincidence.

However, producer Philippa Boyens has stated that Héra was named after the Icelandic actress Hera Hilmarsdóttir (usually credited as Hera Hilmar). I have been unable to find a native Norse name “Hera”, which leads me to believe that the actress was, in fact, named—directly or indirectly—after the Greek goddess. The presence or absence of a diacritic on the e is without significance, in my opinion, as in Greek and Latin it was long as well.

The name Héra is not attested as an Anglo-Saxon name, which is not necessarily fatal: neither is Haleth, as far as I know. However, there is an Old English masculine noun, hēra, meaning “follower” or “servant”. Somehow, I don’t think that’s the meaning the WB creative team was going for. At issue here is that, on philological grounds, Héra is unlikely to be an Anglo-Saxon feminine name. (Which could be a subject for an article in itself.) That said, there is a similar Old English feminine noun, hēre, meaning “dignity”, “majesty”, or “greatness”, that would seem to fit. Tolkien might have written it as “Hére” or “Hérë”, and in Modern English its pronunciation would be virtually indistinguishable from that of Héra.

Speaking of diacritics, the name of the princess is sometimes seen online as “Hèra”, with a grave accent. See the discussion of Old English diacritics earlier in this article to understand why this is wrong—or at least, is contrary to both conventional scholarly and Tolkienian practice.

Olwyn

In the film, Héra has a maid named Olwyn. At first glance, Olwyn has the appearance of a dithematic Old English name ending with the wyn(n) element. However, appearances can be deceiving. If the second element is wyn(n), there is no obvious Old English candidate for the first element. Casting a wider net, however, gives us the Welsh name Olwyn or Olwen. Its meaning is “white footprint”: ol (“footprint”) + gwyn (“white”). Incidentally, it is the name of a character in the Welsh story of Culhwch and Olwen, which is believed to be one of Tolkien’s influences for the tale of Beren and Lúthien.

The Welsh were neighbors of the Anglo-Saxons. However, the issue here is that Tolkien used Welsh in the names of the Hobbits of Buckland, and in the place names around Bree, to demonstrate a Dunlending—or at least Dunlending-adjacent—influence. Is the implication here that Olwyn is herself of mixed Dunlending and Rohirric ancestry, but loyal to the royal household of Rohan? Or is it simply that someone picked a historical name that ends in “wyn” and said, “Looks good to me”?

Lief

There is also a chubby, short-haired blond boy named “Lief”. Lief is not Old English. However, it is the Modern English reflex of the Old English word lēof, meaning “beloved”. Using Tolkien’s conventions for writing the names of Rohan, it would appear as “Léof”. It is a monothematic name that is also attested in Anglo-Saxon literature.

The fact that the name is modernized as “Lief” is not a problem, as I see it. Tolkien was not consistent in his use of Old English, sometimes preferring more modern forms, perhaps for the benefit of his readers, who might otherwise have trouble reading the names out loud. Modernized names include Shadowfax, Snowmane, Snowbourne, Dunharrow, and Harrowdale. Tolkien rarely modernized the personal names of Rohirrim, but Erkenbrand’s name (instead of Eorcanbrand) has been altered from the Old English, apparently for ease of reading.

General Targg

Freca, and later Wulf, have a retainer named General Targg. It is unclear what sort of a name “Targg” is supposed to be. Possibly it is intended to be a Dunlending name. Tolkien wrote very little about the Dunlendish language, except to note that the word Forgoil, an epithet applied to the Rohirrim, means “strawheads”. However, presumably the language of Dunland is related to the language of Bree, which Tolkien represented with names and name elements derived from Welsh.

The name might possibly be related to the word targa (in Old English and several other ancient Germanic languages), meaning a small, round shield—a word which has been borrowed in some form into various other languages, including Celtic languages. Just as the Old English helm had an Old French counterpart, helmet, the Old English targa had an Old French counterpart, target, which is the source of our Modern English word “target”.

Lord Thorne

The Visual Companion mentions a certain Lord Thorne of the Wold. Thorne is a monothematic name, but its form is not clearly Old English. (Or if it is, it is not clear why it should be in the dative case, when names such as “Helm” and “Wulf” are not.) Presumably it means “thorn”, “hawthorn”, or possibly the Runic character “thorn”. Whatever the case may be, the Old English word would be þorn (in the nominative case), which is a masculine noun.

Using Tolkien’s conventions, the name would be written as Thorn. The meaning of the final “e” at the end is unclear. “Thorne” does occur in English place names and as a surname. It was apparently a Middle English variant of “Thorn”. Perhaps the “e” is used here to give the name an “Olde English” look, although paradoxically, for those who are familiar with real Old English, the effect is to make it look less ancient.

Wrot and Shank

There are at least two Orcs in the film, whose names are Wrot and Shank. Both names seem more reminiscent of English than of the Black Speech. In the case of Wrot, the initial wr is suggestive of a Germanic language. Possibly it derives from Old English wrōt, which means “snout”. More likely, I think it is a barely-disguised form of the Modern English word “rot”, meaning “decay” and “putrescence”. It derives from the Old English verb rotian (“to corrupt, putrify”).

The name Shank is probably from the Modern English word, which derives from Old English sceanca. In Old English the word typically referred to the lower leg, although it could occasionally refer to the thigh as well. However, the Orc’s name is likely influenced by modern slang meanings of the word “shank”, which include a makeshift knife, and the act of stabbing someone with such a weapon.

Old Pennicruik

Another character mentioned in the Visual Companion is “Old Pennicruik”, an elderly woman. The form of the name does not appear to be Old English. “Pennicruik” seems to be dithematic, though it seems more like a byname than a conventional Anglo-Saxon name.

The first element is likely pening (“penny”, a coin or a measure of weight), which also appears as penig and pennig, among other variants. The second element looks like the Scots form of the word “crook”. This is believed to be from Old Norse krókr, meaning “hook”, or something that is crooked. If Old English had a cognate word, it is unattested.

The name “Pennicruik” also resembles the Scottish surname Penicuik (or various alternate spellings), which is believed to be of a Brythonic (Celtic) origin, meaning “Cuckoo Hill”.

Ashere

From the 2025 tie-in calendar, we also know that Héra’s horse is named “Ashere”. Most likely this is from Old English Æschere, meaning literally “ash-wood army”, or poetically “spear-band”, as spear shafts were commonly made of ash wood. However, it could also mean “ship-band” for the same reason.

“Ashere” is a reasonable rendering of Æschere for a Modern English-speaking audience, although something like “Ashherë” would be more precise. Tolkien himself created the name “Marhari”, which is presumably reduced from “Marhhari”, and he often did not use the dieresis on the final e of names from Rohan, such as Folcwine, so in that sense “Ashere” does seem like a name Tolkien could have come up with.

Incidentally, Æschere is the name of a character in Beowulf, a beloved counselor of the Danish King Hrōþgār. Æschere is killed by Grendel’s mother in revenge for her son’s death at the hands of Bēowulf.

Lord Frygt

Lastly, over two years ago there was a rumored character said to be named “Lord Frygt”. So far, this character has not been confirmed by Warner Bros. It has been noted that frygt means “fright” in Danish, perhaps suggesting that the character is villainous, and perhaps even non-human. In late Old English the sounds written as g and h often became confused. For instance, the word burg (“fortified town”) was often written as burh or buruh. It is conceivable that the Old English word fryhtu (“fright”) could be written as frygtu or frygto. However, it is a feminine noun.

Another possibility is the Old English neuter noun fyrht, also friht, which means “divination” or “augury”. With metathesis of r and a preceding vowel (a quite common Old English sound change) and confusion of g and h, fyrht could easily become frygt.

Assuming that Lord Frygt is an actual character in the film, however, nothing is known about him, not even whether he is from Rohan or Dunland, or whether he is a Man, Orc, or something else. It is also possible that this rumored character exists, but his name has been changed—perhaps to Lord Thorne, for example.

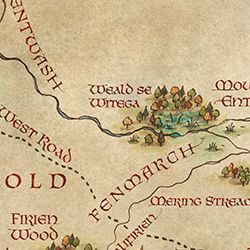

Weald se Witega

Although all of these created names have been names of people or creatures so far, it seems there is at least one place name that has been created for the film. On maps of Rohan that have been distributed for film publicity, there is a wooded area just upstream from the Mouths of Entwash labeled “Weald se Witega”.

This is clearly Old English. The word weald meant “wood”, and survives in the name of The Weald, a wooded upland area in Southern England. A Northern dialectal variant of the same word, wald is the ancestor of Modern English “wold”, which refers to non-wooded upland areas. The word se is the masculine nominative definite article. That is to say, it was one form of the word “the” in Old English. The word wītega means “wise man”, “prophet”, “sage”, or “seer”. In the context of Middle-earth, however, I suspect it refers to a Wizard, or Istar.

The entire phrase “Weald se Witega”, then, may be directly translated as “Wood the Wizard”. It may be translated so, because se wītega is in the nominative (subject) case rather than the genitive (possessive) case. In order to get a translation such as “Wood of the Wizard” or “Wizard’s Wood”—which is what I believe the intent is—one would need to start with the Old English Weald þæs Wītegan or Wītegan Weald.

The Onomastic Outlook

Of these names that have been created for the film so far, I would say there are only two that I could see Tolkien himself creating: Ashere and Lief. I do believe, though, that he would have used Ashere for a man rather than a horse. As for Lief, although I see nothing inherently wrong with it, I believe Tolkien would have used Léof instead, just because we have plenty of other examples of names from Rohan with the same diphthong (vowel combination), including “Léofa”, the byname of King Brytta of Rohan.

With regard to the name of Héra, who is one of the three main characters in the film, and the point-of-view character, I do empathize with the writers and producers who had to come up with a name for her. However, I don’t agree with the name they arrived at, or at least its form.

They could have simply reused “Hild”, the name of Héra’s aunt, but I can understand why they did not. Although the Anglo-Saxons had no problem reusing names, typically they skipped at least one generation, if not two. Also, for audiences watching the film, it would be confusing to have two characters with the same name.

They wanted a name that started with h, to alliterate with Helm, Haleth, Háma, and Hild. I don’t think that requirement was strictly necessary, but I find it understandable. Abandoning it, however, would have allowed them to use “Idis”, the name of Théoden’s daughter whom Tolkien dropped from The Lord of the Rings because she didn’t really offer anything to the story that Éowyn didn’t already have.

Although they have not said as much, it seems the writers and producers also had the requirement that the name of Helm’s daughter be a monothematic name, just like Helm, Haleth, Háma, and Hild. Otherwise, they could easily have given her a dithematic name such as “Herewyn”, “Hathugard”, “Hildeswith”, or “Helmthryth”.

Even with this constraint, I think they still had options in Old English. One name that fits is Hygd, who was the wife of Hygelāc, King of the Geats, in Beowulf. Her name means something like “thoughtful”, and could be pronounced by Modern English-speakers as “Heed”. Another name that fits is, well, Hére (or Hérë). The producers could explain that it is pronounced something like “hair-uh” or “hair-eh”, and we’d be right where we are today, but with less confusion over Greek goddesses. (And, to be fair, probably more confusion over either diacritics or final e’s. But I would find that a fair trade-off.)

Unlike The Lord of the Rings live-action film trilogy, and like Amazon Studios’ The Rings of Power, Warner Bros.’ The War of the Rohirrim is putting flesh on a story of which only the bones exist in Tolkien’s writings. Fans of Tolkien’s works are naturally interested (and concerned) to see how such adaptations extend on what Tolkien himself has written, and whether they feel like they are part of the same world.

Of course, this is all subjective to some extent. However, to me, at least, names are an important part of world-building, and can add to or take away from the verisimilitude of a work of historical fiction, fantasy, or even science fiction. Unfortunately, the names created by Warner Bros. that I have seen so far haven’t given me much cause for optimism in this area. I was more impressed by the brief phrase, Hēo is se wind, in “The Rider”, a song sung by Paris Paloma for the film. This is only one aspect of the film, though, however important it is to me. Hopefully other aspects, such as writing and character development, are done with more care.

Angon

December 9, 2024 at 6:08 amIf “hēra” is a masculine noun, what would be an Anglo-Saxon word for “female follower, female servant”?

Also, Tolkien said that he “anglicized” Hobbit-names by changing their endings, since in Hobbit-names “a” was a masculine ending and “o” and “e” were feminine. So if the name Hére, as you suggest, would be correct, can’t we assume that it was “anglicized” into Héra?

Austrawandil

December 31, 2024 at 6:29 amThere are specific words for female servant, such as þēowe, þēowen, þignen/þīnen, and wencel. However, I am not aware of a feminine counterpart specifically of hēra. Likely it would be something like hēre, though, if it existed, if not hēren(e) or hērestre.

Certainly it is not unheard of to modernize (or Latinize) names. Disa, for instance, is the name of a Swedish princess (although likely the original form of her name was Dís). However, there is still the inconsistency to account for. Héra’s brother’s name is Háma, not Hámo. Perhaps we have Háma’s name from Rohirric tradition (understanding that the “Rohirric” we have is just the Old English “translation” of the original true Rohirric names), and Héra’s name comes from some other tradition, such as a Hobbitish, Rivendell, or Gondorian document or song, or perhaps an immortal being knew Héra, and that was the form of her name at the time. (Although I think the names Tolkien gave us of the Rohirrim and their ancestors were meant to be the contemporary forms of their names; otherwise Vinitharya would be Winedhere and Marhwini would be Mearhwine.)

Andrew Laubacher

December 21, 2024 at 6:58 amAh, but how would Héra’s full name be rendered? Héra Helmsdóttir? Or perhaps Héra Helmsdohtor?

Austrawandil

December 31, 2024 at 5:16 amAs far as any of her acquaintances would be concerned, just “Héra” is her full name. A patronymic could be added, but it would be considered an additional name (byname), not part of her full name. The form would probably be “Héra Helmesdohtor”. This is, of course, assuming the form “Héra” works without alteration.