War of the Rohirrim: Streaming and Other News

The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim, which was released in theaters last December, is now being made available on Warner Bros.’ Max streaming service, as well as airing on HBO for the first time. In addition, the film is being rolled out on Blu-ray and 4K Ultra-HD, for those who wish to own physical copies of the film. In addition, the book The Art of The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim has been published. Finally, since seeing the film, I have some additions to make to The War of the Rohirrim Onomasticon.

Streaming Digital and Cable Distribution

The Warner Bros. film The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim is being made available for streaming on demand on the Max streaming service (owned by Warner Bros. Discovery) beginning on Friday, February 28. It has already been available on Amazon Prime Video since late December, albeit at extra cost. It will be available at no extra cost for Max subscribers. In addition, the film is premiering on the HBO channel on Saturday, March 1. The film made around $20.5 million in theaters, which is little more than two-thirds of its production cost of $30 million. Whether it will perform any better on streaming remains to be seen.

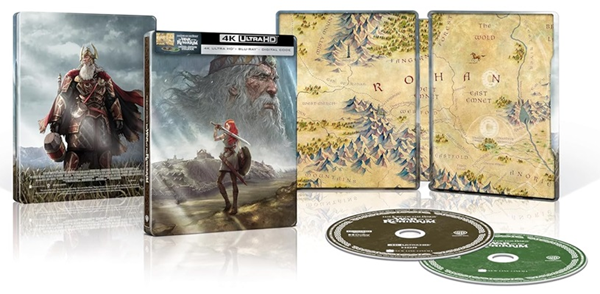

Blu-ray and 4K Ultra-HD

The War of the Rohirrim has been available on physical media since February 18. Editions include regular 1080p Blu-ray and 4K UHD Blu-ray. Also, a limited edition SteelBook is available. The SteelBook includes both 1080p and 4K UHD Blu-ray discs, and a digital copy of the film. The other editions include a voucher for a digital copy of the film. The SteelBook is region-free, meaning it may be played in any 4K UHD Blu-ray player, no matter in which part of the world it was purchased.

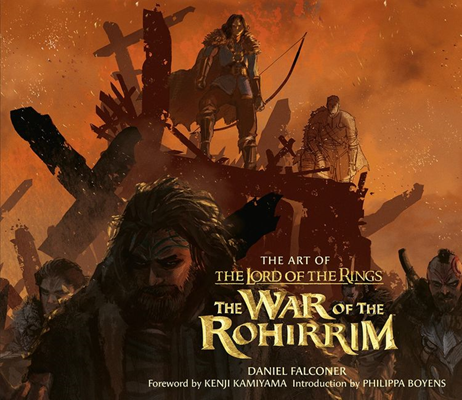

The Art of The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim

Also on February 18, The Art of The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim was published. The book was written and compiled by Wētā Workshop conceptual artist Daniel Falconer, who worked on The War of the Rohirrim, and also drew conceptual art for the live-action films. This book contains over a thousand sketches, drawings, and other works of art created for the film’s production. This title joins The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim Official Visual Companion and The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim Official Coloring Book as official movie tie-in books, both of which were released on November 5, 2024.

The War of the Rohirrim Onomasticon, Part II (Addendum)

The first part of the Onomasticon was published before the release of the film, but after most of the character names were known. Since the release of the film, there is a little bit more that may be added to complete the Onomasticon for the film.

Héra

Of course, the name Héra has been known for some time, and I have written about it several times before. However, there is still more I have to say concerning it. First, I would like to say that I am no longer certain of the reality of the Old English feminine noun hēre. It does appear in An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (better known as the Bosworth-Toller dictionary) here and here. The latter entry speculates that hére might actually be a form of the word hér, which is defined as an adjective meaning “noble”, among other things. A feminine noun hēre also occurs in A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary by J. R. Clark Hall. However, both dictionaries were first published in the 19th century. Although they are generally useful, they may be outdated in some respects. The current state of the art is the Dictionary of Old English, which is an electronic resource available only to subscribers.

The Art of The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim gives us a little bit more insight into the decision to give Helm’s daughter the name “Héra”. It says that “lots of names” were suggested, and mentions “Helga” and “Hilda” as examples. I will note that, although they are Germanic names, neither is Old English in form. The Old English form of “Hilda” is “Hild”, which is also the name of Helm’s sister. Perhaps the writers could have used “Hild” for Héra, since Helm’s sister is not directly mentioned in the film. However, it would have been confusing for Tolkien fans already familiar with the story. Also, Fréaláf is called “Fréaláf Hildeson” during his coronation, which would have been confusing if his cousin was named “Hild”.

The account of the producers’ interaction with “scholars” (also in the Art book) is somewhat more illuminating, but I also find it confusing. As best as I can understand it, the producers submitted the name “Hera” for advice on how it could be understood as an Old English name. The response they received, apparently, was that it could be seen as a combination of ā (“ever”) and hēr (“noble”). There are several problems with this. One is that the syntax is unusual. In compounds ā is always prefixed, as far as I am aware, which would result in the name “Áhér”, rather than “Hérá” (just as in Modern English we would say “evergreen” rather than “greenever”).

The book gives “Héráh” as being the spelling that is “technically” correct. Technically, āh means “has” or “owns”, or is another spelling of āg, a supposed prefix (in āglāc and āglǣċa) whose meaning is uncertain. Neither makes sense in this context. I believe “Héráh”, rather than being a precise Old English spelling, is just a phonetic guide for speakers of Modern English, to indicate that the second syllable should receive equal (or secondary) stress. Most speakers of Modern English would be inclined to leave the second syllable unstressed (and also pronounce it as a schwa: /ə/) when the spelling is “Héra”.

Another issue with the suggested “ever noble” etymology is that the elements ā and hēr are unusual, if not unheard of, in Anglo-Saxon names. Although there are a number of Anglo-Saxon names that begin with “Her-”, this is usually understood as being the word here (“army”). Furthermore, it is questionable that hēr (as an adjective meaning “noble”) existed in Old English. Modern Standard German hehr, which can mean “noble”, is descended from Old High German hēr, and the same form of the word existed in Old Saxon. The problem is that the Old English cognate was hār, and it usually meant “gray-haired” (“hoary” in Modern English). Old English her is attested in the compound herlic, supposedly meaning “noble” according to the Bosworth-Toller dictionary, but even the Clark Hall dictionary says it’s from herelic, meaning “martial”.

Still left unaddressed is whether the producers themselves ever came up with any dithematic (two-element) names for the character. That said, “Hérá”, with the meaning “ever noble”, as apparently interpreted by scholars of Old English, is itself a dithematic name. Given that the producers seemed willing to accept it, I see no reason why they should not have considered other dithematic names. Ignoring the previous paragraph, one possible name could be Hérthrýth, with the meaning “noble strength”.

One element that is attested in some Anglo-Saxon names is hēah (“high”, “sublime”, “illustrious”, etc.). Although it is not terribly common as the first element of a name, the feminine name Heaburg (“high fortress”) is attested. Other possibilities include Héathrýth, Héagýth, Héaswíth, Héaflǽd, Héawaru, Héarún, Héagifu, Héacwén, Héahild, Héawyn, Héalufu, Héamǽg—and not much more. Unfortunately, we’re somewhat limited by the number of attested names of Anglo-Saxon women—or at least, by female names recorded in Old English.

Some other elements might be assumed to have occurred at some point during the Anglo-Saxon age, such as beorg and līþe, because they occurred in Norse or Continental Germanic feminine names, but we have no record of them in given names in Old English records. And, in addition to “Héa-” as the initial element, there are others that I have mentioned previously, such as “Here-”, “Heru-”, “Hathu-”, “Hilde-”, “Hyge-”, and so on. Again, we are limited by the attested names.

Finally, in coming up with names for the Rohirrim, I would argue that we are not necessarily limited by attested names or name elements, as Tolkien himself was not. Many of his names—particularly names of Kings of Rohan—were simply poetic words for leaders of some sort. Other names are also simply attested Old English words, such as Fastred (OE fæstrǣd, “steadfast”). As an example, the Old English word lind was a feminine noun that meant “linden tree”, or poetically, “shield”. So, even if they are not attested in Old English as names, such names as Hildelind or Hathulind (both meaning “battle shield”) would seem to be suitable for women of Rohan. Or one could use a first element such as holt (“copse”, “wood”) and come up with a name such as Holtswíth (“forest” + “strong”).

Olwyn

I have previously discussed the name “Olwyn”. The Art of The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim adds the information that the character was known as “Solwyn” in previous iterations of the script. I’m not certain why her name was changed, as it is distinctive either way. I don’t think anyone would confuse her for Saruman. The name “Solwyn”—or rather “Sólwyn”—has the advantage that it actually has a meaning in Old English: “sun joy”. That the Old English word—or at least, one of several words—for “sun” coincides with the Latin word for the same is perhaps partly incidental, but also partly due to a common inheritance from a Proto-Indo-European root word. Of course, the more common Old English word was sunne (also somewhat related), but sōl was used poetically, and hence it makes sense as a name element, even if it is not attested.

As I mentioned previously, “Olwyn” makes little sense as an Old English name, but it is a Welsh name. According to Tolkien’s conceit of using historical languages to represent different cultures in his legendarium, one would then expect “Olwyn” to be a Dunlending name. The Dunlendings were related to the folk of Bree, where place names often incorporated Celtic elements. Also, the Stoors spent time in Dunland, and afterwards made up much of the folk of Buckland, which was reflected in Celtic name elements of the Hobbits who lived there, such as the given name of Meriadoc Brandybuck. Given that Olwyn apparently once lived near the border of Dunland, it may make sense that she grew up in a mixed culture in which Dunlending names were not uncommon.

Fryght, Lord of Westfold

Lord Fryght’s name appears in the credits to the film. Previously it was reported as “Lord Frygt”. Presumably it was either misreported, or later changed. For a long time all that was known about this character was the name and the voice actor who played him. Naturally, then, speculation surrounded his name. As it turned out, far from being a frightening character, Lord Fryght is a frightened character. His name comes from the fact that before he had a name, he was referred to in production as “Anxious Lord”. “Fryght” is apparently a modernized form of Old English fryhtu, an alternative form of fyrhtu (“fright”).

Pryme, Lord of the Folde

Lord Pryme is said to be mentioned in the script, although I don’t recall offhand where his name was mentioned. Of all the characters in The War of the Rohirrim, Lord Pryme’s name is the most inscrutable to me, assuming that it is supposed to be Old English. Ignoring that assumption, it seems to be merely an archaic spelling of “prime”, just as “Thorne” is an archaic spelling of “thorn”. The word “prime” is ultimately from Latin prīmus (“first”). Presumably it bears no relation to Amazon’s streaming service, or to the Transformers entertainment franchise. In fact, the word prīm does occur in Old English, alone and in the compound prīmsang, which is the first Catholic religious service of the day, occurring at six o’clock. Six o’clock was considered the first hour of the day.

Curiously, relatively few words begin with p in most Germanic languages, and in many cases where they do occur, they are borrowed words. The reason for this is that few Proto-Indo-European words began with *b (as reconstructed), and Proto-Indo-European *b regularly became Proto-Germanic *p. Why this blind spot occurred in Proto-Indo-European, however, remains a mystery.

Gramhere, Lord of Westemnet

Lord Gramhere’s name is seen on Lief’s scroll in the film. I believe this works well as a name for a lord of Rohan. It would appear to mean “fierce army”. The first element is not well attested in names—certainly not in Old English, at any rate. However, in Tolkien’s works Gram was the name of Helm Hammerhand’s father, so as a Rohirric name I see no objections to it.

Everbrand, Lord of Eastemnet

Lord Everbrand’s name is also seen on Lief’s scroll in the film. Again, I think this name works well. Technically it should be “Eoforbrand” in Old English (“boar sword”). The element brand had the same basic meaning as in Modern English: something that is lit on fire. However, in poetry it was used metaphorically of a sword, since sword blades reflect light as if they themselves are lit up. Since it was used in that manner in poetry, it was also used in that manner in given names. The element eofor (“boar”) has been modernized to “ever” for ease of pronunciation. Tolkien himself names one of Brego’s three sons “Eofor”—the one Éomer is descended from. However, he modernizes the element in the place name “Everholt” (“boar wood”). The same element also occurs in the name “Everard”, used in the Shire.

Weald se Witega

I had previously translated this place as “Wood of the Wizard”, or “Wood of the Istar”. However, after having seen the film, such a translation makes no sense. Wizards are mentioned in the film, but not in reference to this particular location. However, the actual meaning of this place name dawned on me after I began researching the etymology of witan (which see below).

The word wītega has a very similar meaning to Old English wita or Middle English wysarde. It could mean “wise man” or “sage”. However, it had the additional meaning of “prophet” or “seer”. The reconstructed Proto-Germanic form is *wītagô, the Proto-West Germanic form is *wītagō, and the Anglo-Frisian form is *wītægā. (The ô in the Proto-Germanic form represents a “trimor(a)ic”, or “overlong” vowel—a vowel held for half as long again as an ordinary, or “bimor(a)ic”, long vowel.) A cognate form, by way of Middle High German and Middle Dutch, is the word “wiseacre”. The Old English word wītega is not spoken in the film, The War of the Rohirrim, but it appears on the map seen at the beginning of the film, in the location called “Weald se Witega”.

The original Proto-Indo-European verb *weyd-, with the meaning “to see”, entered Proto-Germanic as *wītaną (also reconstructed as *wītanan: the ą represents a nasalized a sound). The verb acquired the secondary sense “to blame” or “to punish”, which is what the verb wītan (notice the long ī) meant in Old English. However, by then the word wītega had gone its own way, retaining the original meaning intact. A wītega, then, is not just “one who knows”, but also “one who sees”—literally, a “seer”. Taken literally, then, this may be an apt description of a creature that is known for seeing: the Watcher in the water.

The verb “watch” comes from Old English wæċċan, ultimately from Proto-Germanic *wakjaną. Although one could hypothesize an Old English ancestor form *wæċċere, the word wacchere, wachere, wacher, etc. was first attested in Middle English. In Old English the more common word was weard, from Proto-Germanic *wardaz, meaning a “watch” or a “guard”. Both words (“watch” and “ward”) come from different Indo-European roots, apparently unrelated to *weyd-.

My revised translation, then, would be something like “Wood of the Seer”, or indeed “Wood of the Watcher”. This is close to the translation given in The Art of The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim, which is “Forest of the Guardian”. (Of course, they did not wish to use the word “Watcher” in order to avoid giving away too much.) My previous comments on the grammar of the name still apply.

Witan

In The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim, Héra hears from her brother Háma that Freca, lord of the West-march, has called a witan. Since witan is not a word commonly in use in Modern English, viewers of the film may wonder exactly what a witan is. The word does not actually occur in The Lord of the Rings. The relevant section, from Appendix A, is here:

…There was at that time a man named Freca, who claimed descent from King Fréawine, though he had, men said, much Dunlendish blood, and was dark-haired. He grew rich and powerful, having wide lands on either side of the Adorn. Near its source he made himself a stronghold and paid little heed to the king. Helm mistrusted him, but called him to his councils; and he came when it pleased him.

To one of these councils Freca rode with many men, and he asked the hand of Helm’s daughter for his son Wulf. But Helm said: “You have grown big since you were last here; but it is mostly fat, I guess”; and men laughed at that, for Freca was wide in the belt.

—The Lord of the Rings Appendix A: “Annals of the Kings and Rulers”, II – “The House of Eorl”

The word in this passage that corresponds (more or less) to witan is “council”. The word witan is an Old English word. In fact, it is (presumably in this case) the plural of the noun wita, which means “wise man”, or “advisor”. The witan, then, are the “wise men”, or “advisors” with whom King Helm consults before making important decisions. But witan does not exactly mean “council” in Old English.

The usual word for council in Old English was ġemōt. This word has come down to us in Modern English as “moot”, albeit usually with an altered meaning. However, Tolkien resuscitated its older meaning, for example in the term “Entmoot”, and in Tolkien fandom these days the term “moot” is commonly used to refer to a meeting or gathering of fans. (Incidentally, the word “moot” is related to the word “meet”, the difference in the vowels being caused by a sound change known as “i-mutation”. But that may be a subject for a different article.) Scholars of Anglo-Saxon England commonly refer to the royal council as the witenaġemōt—literally, the “meeting of advisors”, or the “meeting of wise men”. However, the ġemōt is the council itself, and the witan are the people who attend the meeting.

Although the fact is not mentioned in the film itself, Brian Cox, who voices Helm, has said that Helm was elected. This statement has caused some raised eyebrows, but in Anglo-Saxon England the kings were in fact elected by the witan. (Some may object to the idea of the Rohirrim being represented by the historical Anglo-Saxons. However, whatever one thinks Tolkien’s intentions may have been, it is clear from interviews that Philippa Boyens and many others who have worked on the New Line/WB films do take the Anglo-Saxons as at least one major influence for the Rohirrim.) The elections by the witan were different from elections as we may think of them, however. For one thing, a major consideration of all candidates was the strength of their claim to the throne. In practice, all else being equal, the witan would give strongest weight to the claim of the eldest son of the late king. Not only did the witan have the right to elect the king, but they also had the right to depose the king. However, they did not exercise this right except in unusual circumstances.

Although the word wita (and its various declensions, such as witan, witum, and witena) has not survived into Modern English, many related words have, such as “wit”, “wisdom”, “wise”, and “wizard”. Even more distantly related are Latinate words such as “view”, “survey”, “vision”, “visit”, and “video”. All of these words come from a Proto-Indo-European root reconstructed as *weyd-, and with the meaning “to see”. All the Latinate words are related to the Latin verb vidēre (“to see”).

In the Germanic languages this root became subject to a semantic shift. The perfective form of the verb, with the meaning “have seen”, became the basis of a verb with the present-tense meaning “know”. This verb is believed to have had the infinitive form *witaną (also reconstructed as *witanan) in Proto-Germanic, which became witan by Old English (notice the short i; not to be confused with the plural noun witan). It had the specific meaning, “to be aware of some fact or information”. This verb survived into Early Modern English, e.g. “I wot not who hath done this thing,” and “I wist not whence they were”. It is generally regarded as archaic at present, but it still survives in some words and phrases such as “to wit” and “unwitting”.

The noun wita, then, is “one who knows”. In Proto-Germanic it would have been *witô, with the masculine agentive suffix *-ô added to the root of the verb. This would have become *witō in Proto-West Germanic, *witā in Anglo-Frisian, and wita around the time of written Old English. The form wita is the singular form in the nominative (subject) case. The corresponding plural form, as mentioned, is witan. And the genitive plural form is witena (“of the wise men”, or “of the advisors”), which occurs in the term witenaġemōt (“meeting of wise men”).

No Comments